via Big Think by Paul Ratner

During the so-called Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, European intellectuals came to believe strongly in the power of reason as the mechanism for controlling the world. The scientific method flourished. Ideals like liberty, progress, constitutional government and separation of church and state came to the forefront. At the onset of this time, Isaac Newton introduced his laws of motion, including the law of universal gravitation, which explained how the whole solar system operated. This set the stage for the concept of a clockwork universe, which became popular especially in deist circles.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

A close reading of a classic religious poem

‘Prayer (I)’ is one of George Herbert’s best-loved poems. Herbert (1593-1633), who sent his poems to a friend Nicholas Ferrar with the instruction that his friend should publish them or destroy them, depending on whether he thought they were any good, is now revered as one of the greatest poets of the Early Modern period. ‘Prayer (I)’ is a relatively straightforward poem, but its language and references require some analysis and unpicking.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Andrea James

Woodworker Matthias Wandel has mice in his workshop, and he wanted to see how small a hole mice could crawl through. But after setting up his ingenious little test, a challenger appears: the wily shrew!

Continue reading and watch two short videos

==============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: the Times Literary Supplement

Naomi Wolf considers the influence of Oscar Wilde on Edith Wharton

In 1903 Edith Wharton met the writer Vernon Lee in Italy, and started reading John Addington Symonds. By 1905 she had begun an intimate friendship with Henry James and the circle of male homosexual writers around him, and was soon reading Walt Whitman and Nietzsche, while having an affair with the American journalist Morton Fullerton. Through these influences, Wharton was drawn away from American discourses about sexuality in fiction (which were generally moralistic in this period, regardless of the gender of the writer), and towards British and European aestheticism and sexual liberation. It is after this period that we begin to see the multiple echoes of Oscar Wilde in her work. Wharton used Wilde in order to engage in a necessary, indeed central, argument about what happens to the aestheticist and sexual liberationist project once it is undertaken by heterosexual women.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Guardian by Blake Morrison

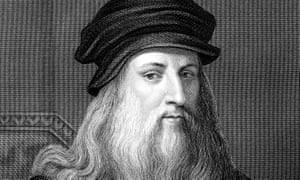

A 19th-century engraving of Leonardo. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

In 1501, desperate for Leonardo to paint her portrait, the immensely rich Isabella d’Este employed a friar to act as go-between. The friar met Leonardo in Florence but found his lifestyle “irregular and uncertain” and couldn’t pin him down. “Mathematical experiments have absorbed his thoughts so entirely that he cannot bear the sight of a paintbrush,” Isabella was told. With promises he’d get round to it eventually, Leonardo kept her dangling for another three years. Pushy to the end, she changed tack and asked him for a painting of Jesus instead. Even then, he didn’t come up with the goods.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

A commentary on Shakespeare’s 116th sonnet

A real wedding favourite, this: Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116. ‘Let me not to the marriage of true minds’ is a popular poem to be recited at wedding readings, and yet, as many commentators have pointed out, there is something odd about a heterosexual couple celebrating their marriage (of bodies as well as minds) by reading aloud this paean to gay love, celebrating a marriage of minds but not bodies (no gay marriage in Shakespeare’s time). This makes the poem, along with Robert Frost’s often-misunderstood ‘The Road Not Taken’, a candidate for the most-misinterpreted poem in English. So let’s take a closer look at this poem by way of summary and analysis.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Guardian by Piers Torday

Opening a new chapter in children’s reading … Devin Stanfield as Kay in the BBC’s 1984 adaptation of The Box of Delights. Photograph: BBC Pictures Archives

My first memory of “appointment to view” TV is as indelible as it is vivid. It was the final episode of the BBC’s adaptation of John Masefield’s The Box of Delights, which I caught only by imploring my mother to let me stay for another half an hour while visiting a friend. The early special effects in the style of Doctor Who were as stardust to my young eyes; I still recall the thrill of watching Robert Stephens (as the villainous Abner Brown) fall to his watery fate. It wasn’t only the state-of-the-art animation and the compelling performances that captured my imagination, but also the magic of the story.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

A commentary on Shakespeare’s 105th sonnet

‘Let not my love be called idolatry’, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 105, sees the Bard continue to meditate on the nature of his love for the Fair Youth. Here’s a reminder of Sonnet 105 before we proceed to a commentary on its language and meaning.

Let not my love be called idolatry,

Nor my beloved as an idol show,

Since all alike my songs and praises be

To one, of one, still such, and ever so.

Kind is my love to-day, to-morrow kind,

Still constant in a wondrous excellence;

Therefore my verse to constancy confined,

One thing expressing, leaves out difference.

Fair, kind, and true, is all my argument,

Fair, kind, and true, varying to other words;

And in this change is my invention spent,

Three themes in one, which wondrous scope affords.

Fair, kind, and true, have often lived alone,

Which three till now, never kept seat in one.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment