vie the Guardian by Brian Switek

This herbivorous creature could be the missing link in the dinosaur family tree, changing everything we think we know about their evolution

Chilesaurus diegosuarez, from the Late Jurassic period.

Photograph: Gabriel L O/AFP/Getty Images

Chilesaurus doesn’t look like the kind of dinosaur that would kick up much of a fuss. The Jurassic saurian – named for the country, not the tasty peppers – was a small, bipedal herbivore that munched on plants over 150m years ago. It didn’t have nasty teeth, crazy horns, or the immense body size that typically launch the careers of Mesozoic celebrities. The creature’s secret is more subtle, and plays into a controversial reshuffling of the dinosaur family tree.

Continue reading

=============================

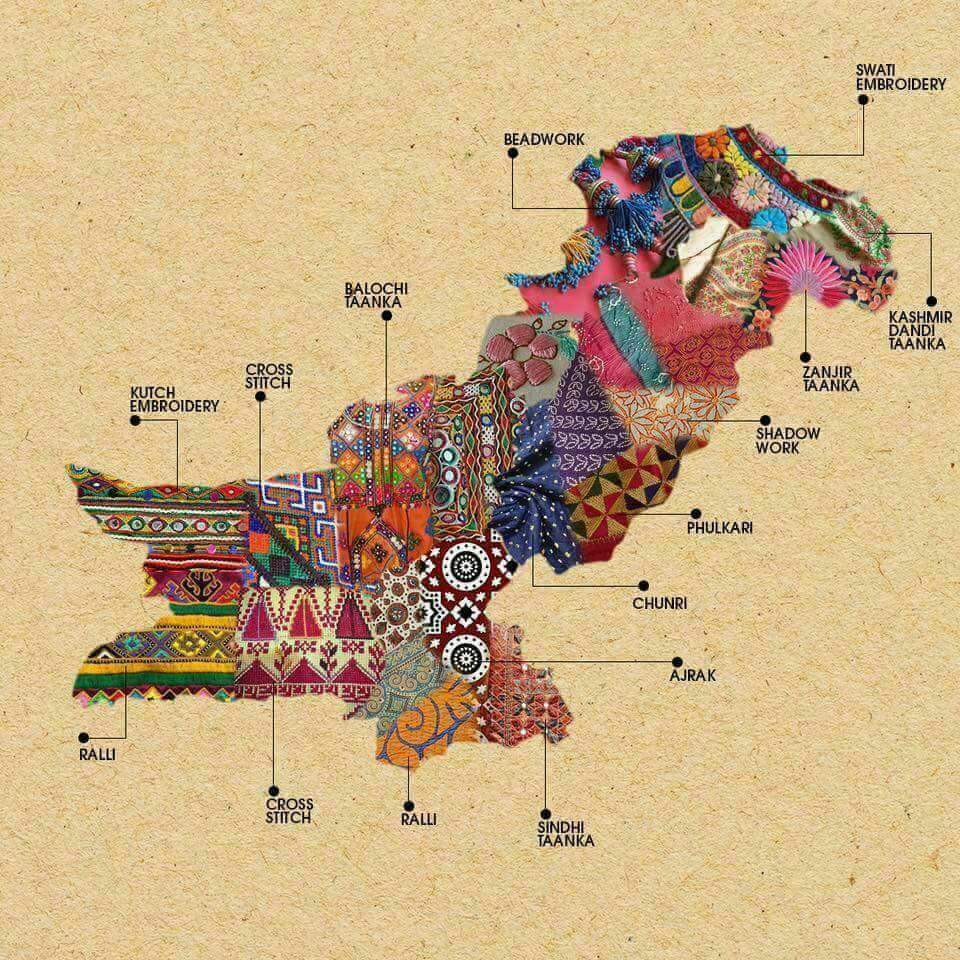

Map of local embroidery techniques in Pakistan

via Boing Boing by Rob Beschizza

As posted to Twitter by Saima Mir, and likely sourced from Generation; but who’s the artist?

=============================

Geneticists trace humble apple’s exotic lineage all the way to the Silk Road

via the Guardian by Nicola Davis

The fruit’s evolutionary history has been unpicked for the first time by studying a range of wild and cultivated apples from China to North America

The apples we know today, varieties of the species Malus domestica, have long been known to have descended from a species of wild apple from central Asia, known as Malus sieversii.

Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

Continue reading

=============================

Artificial intelligence identifies plant species by looking at them

via Boing Boing by David Pescovitz

Machine learning algorithms have successfully identified plant species in massive herbaria just by looking at the dried specimens. According to researchers, similar AI approaches could also be used identify the likes of fly larvae and plant fossils.

Continue reading

=============================

Here’s an On-Screen Dictionary for Fictional Characters, Places, and Terms

via Make Use Of by Saikat Basu

IBM Watson counted more than 2,000 characters in the Game of Thrones book series. Now imagine trying to track them all and their bios in your head. Tough.

This is where The Fictionary can be a huge help:

“A free look-up capable custom e-book dictionary of fictitious terms, places, and people in literature. Created by author provided content or community wikis.”

Yes, it is a dictionary for fiction literature. Install these sets of custom dictionaries and understand fictitious terms in e-readers and Kindles. Now, those 2,000 characters fighting and dying throughout the seven kingdoms will seem more familiar.

Continue reading

I have not tried this yet but it does sound like a wonderful idea.

=============================

Germans must remember the truth about Ukraine – for their own sake

via Eurozine by Timothy Snyder

Ukraine in European dialogue

Post-revolutionary Ukrainian society displays a unique mix of hope, enthusiasm, social creativity, collective trauma of war, radicalism and disillusionment. With the Maidan becoming history, this focal point – in cooperation with the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) – explores the new challenges facing the young democracy and its place in Europe.

Don’t fall for the official Russian line on WWII, historian Timothy Snyder warns German MPs in a speech at the Bundestag. In the debate over Germany's historical responsibility for its wartime actions in Ukraine, ‘Germany cannot afford to get major issues of its history wrong.’

Continue reading

This item enlightened me about a period of history about which I knew little or nothing before reading it.

=============================

Why do cephalopods produce ink? And what's ink made of, anyway?

via the Guardian by Mark Carnall

Surprisingly, there’s still a lot we don’t know about ink and inking.

Photograph: Hilary Moore/Getty Images

Cephalopods, the group of molluscs that includes octopuses, cuttlefish, squids, ammonites, nautiluses and belemnites, are a weird bunch. Not only are they strange when anatomically compared to their shelled relatives like bivalves, snails and chitons but their evolution, physiology and behaviour makes them almost as interesting as vertebrates (I’m kidding, they’re way more interesting).

Continue reading

=============================

Big bad wolves and other scary stuff

via An Awfully Big Blog Adventure by Stroppy Author

A three-year-old I know, MicroB, likes dinosaurs - but she's also scared of them. She likes to read stories about dinosaurs, and play with them, and go to see them at the museum. But then she is afraid they will come in her room when she is asleep and sometimes she has nightmares about them. Today she asked me to read The Enormous Crocodile, even though she's rather scared of being eaten by a crocodile (understandably). And of course we read lots of books with big bad wolves in. One night she asked me to draw a big bad wolf on the chalkboard door in her bedroom. It didn't seem like a good idea, but I did it. And when we go to Lammas Land, she likes to go over the troll bridge and then peer underneath to see which troll didn't eat her this time. It seems she's challenging herself with these fears.

Continue reading

=============================

This panda-shaped solar farm sets a new bar for cute creativity

via Boing Boing by Andrea James

Panda Power Plant in Datong, China is a multiphase solar farm building panda-shaped solar arrays.

Continue reading

=============================

Hampering Threadlike Pressure: A New Biography of George Eliot

via Arts & Letters Daily: Paul Delany in Los Angeles Review of Books

“Great literature has always been the […] Forgiveness of Sin,” W.B. Yeats wrote in 1901, “and when we find it becoming the Accusation of Sin, as in George Eliot […] literature has begun to change into something else.” Eliot’s problem, as Yeats recognized, lay in finding a balance between her conflicting instincts: to sympathize with people and to judge them. Eliot felt it her duty to cultivate “direct fellow-feeling” and be generous toward the little people, even though, as she well knew, they had often failed to be generous to her.

The Eliot problem helps to explain why some 15 biographies of her have appeared over the past 30 years or so. (There doesn’t seem to be any Dickens problem or Trollope problem that requires such obsessive attention.) Philip Davis’s The Transferred Life of George Eliot is the latest entry in this series, and it is a brief for the greatness of George Eliot as a thinker, a novelist, and a person, and thus a justification of literature as she chose to write it. Davis’s particular approach is “to understand [Eliot’s] life through her work because it was to her work that she transferred and dedicated her life.” What defines Eliot, in Davis’s view, is “her commitment to the role of imaginative sympathy in understanding,” which makes her not just a great writer, but also an admirable person.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment