via OUP Blog by Piers Locke and Jane Buckingham

Throughout history and across cultures elephants have amazed and perplexed us, acquiring a plethora of meanings and purposes as our interactions have developed. They have been feared and hunted as wild animals, attacked and killed as dangerous pests, while also laboring for humans as vehicles, engineering devices, and weapons of war. Elephants have also been exploited for the luxury commodity of ivory, laughed at as objects of entertainment, and venerated as subjects of myth and symbolism. Throughout history humans have forged deeply effective connections with elephants, both as intimate companions and as spectacles of wonder.

Continue reading

===================================

via An Awfully Big Blog Adventure by Catherine Butler

Here’s a harebrained theory for you. It applies only to the southern half of the country (the North needs a theory of its own), so please draw a line across your imaginary map of Britain, running from the Mersey to the Humber.

The truncated realm before you is a fantasy landscape. Oxford is its symbolic centre, and marks the place where two great tectonic plates meet and clash. (This seismic activity explains why, from Lewis Carroll, through Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman and Frances Hardinge, Oxford has produced so much seminal fantasy.)

Beyond, the country is divided on East-West lines. To the West, fantasy is about myth and the land. Its locus is the standing stone, the ancient well, the cave; its magic is nature magic; its past is the deep past. This is the fantasy I've always felt closest to, and most wished to write.

But I also love the fantasy of the East. Here is the fantasy of time slips and family ghosts. Its locus is the grand house; its magic is memory and dream magic; its past is the historical past. If the West has Alan Garner, Catherine Fisher, Jenny Nimmo and Susan Cooper (albeit she has a foot in both camps, geographically), the East has Lucy M. Boston, Philippa Pearce, Joan G. Robinson, and Rudyard Kipling (although he, too, is an ambiguous case).

Continue reading PLEASE

===================================

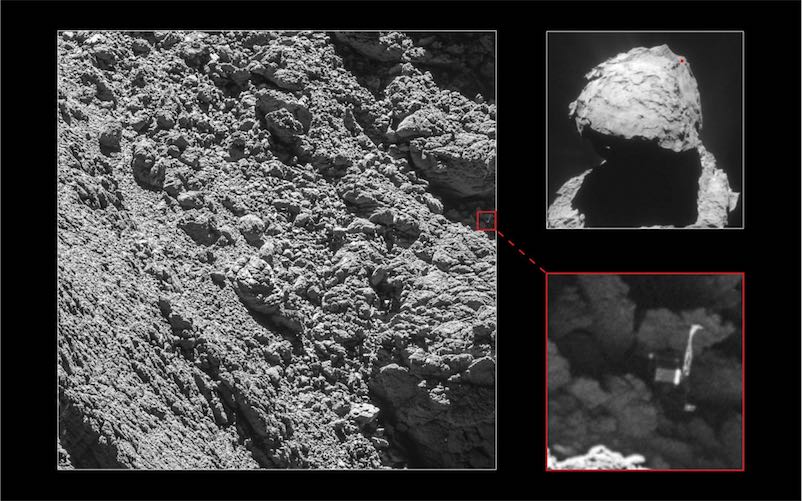

via Boing Boing by David Pescovitz

In 2014, the Philae space probe left the Rosetta spacecraft and descended to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Unfortunately, Philae missed its landing due to an anchor mishap, bounced around, and then vanished. On Sunday, just a few weeks before Rosetta's expected crash into the comet and the end of the mission, Cecilia Tubiana of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research was scouring new images of the comet transmitted from Rosetta and noticed the dishwasher-sized probe in a crack.

Continue reading

===================================

via the Guardian by Derek Niemann

Early Tudor stained glass in Madingley church, showing, left, a figure representing charity and justice, and, right, Charlemagne.

Photograph: Sarah Niemann

A time-travelling Tudor peasant might return to the place of their birth and find reassurance in the sight of Madingley’s medieval church. They could stand before its sturdy tower and run their fingers over stones embedded in mortar, as I did, then step inside to rediscover the font where they were baptised, and look up for re-acquaintance with exquisitely detailed medieval figures floating in stained glass.

But a hard stare into the nettled field beside the churchyard would make them wonder where their village had gone. The 18th century owners of Madingley Hall, which is about four miles from the centre of Cambridge, desired an estate with a view, and that view did not include a village street. So by the middle of the century the people had been evicted from their homes, their houses razed to the ground. I came to search for evidence of this lost community and found it.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Mark Frauenfelder

Great episode of What's my Line from 1964 in which Elizabeth Taylor uses a squeaky voice in an attempt to trick the blindfolded panelists.

===================================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Simon Makin in Scientific American

For illustration purposes only. Credit: PETER DAZELEY Getty Images

Most people think of memory as a faithful, if incomplete, recording of the past – a kind of multimedia storehouse of experiences. But psychologists, neuroscientists and lawyers know better. Eyewitness testimony, for instance, is now known to be notoriously unreliable. This is because memory is not just about retrieving stored information. Our minds normally construct memories using a blend of remembered experiences and knowledge about the world. Our memories can be frazzled, though, by new experiences that end up tangling the past and the present.

Continue reading

===================================

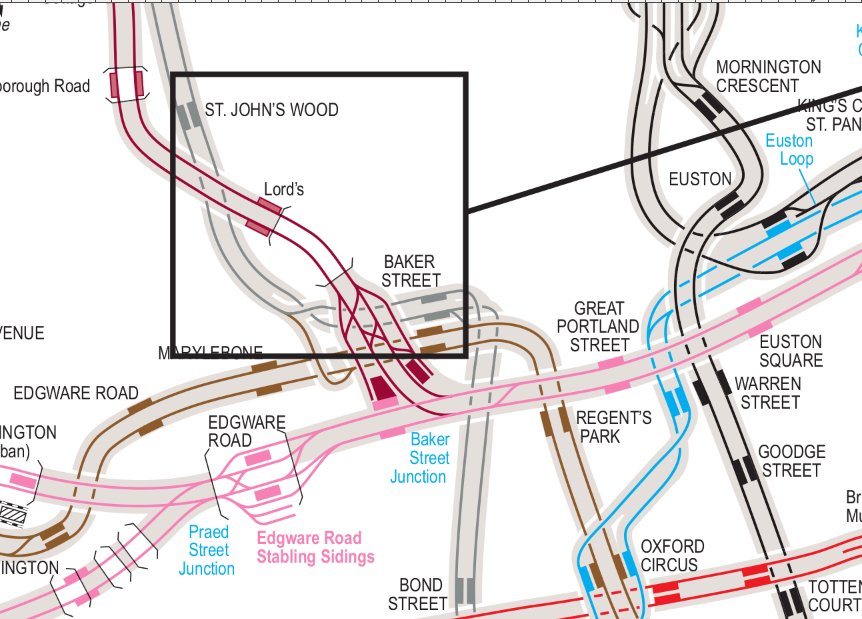

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

The Transport for London tube map, building on Harry Beck's pioneering work in 1931, is rightly hailed as a masterpiece of simplification and clarity in data visualisation.

Continue reading

===================================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Robert F. Worth in The New York Review of Books

Sometime around the year 1314, a retired Egyptian bureaucrat named Shihab al-Din al-Nuwayri began writing a compendium of all knowledge, under the appealingly reckless title The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition. It would eventually total more than 9,000 pages in thirty volumes, covering all of human history from Adam onward, all known plants and animals, geography, law, the arts of government and war, poetry, recipes, jokes, and of course, the revelations of Islam.

Continue reading

===================================

via OUP Blog Zackery Cuevas and Cassandra Gill

About two thousand years ago, fifty thousand people filled the Colosseum in Rome to participate in one of the most fascinating and violent events to ever take place in the ancient world. Gladiator fights were the phenomenon of their day – a celebration of courage, endurance, bravery, and violence against a backdrop of fame, fortune, and social scrutiny. Today, over 6 million people flock every year to admire the Colosseum, but what took place within those ancient walls has long been a matter of both scholarly debate and general interest.

Continue reading

===================================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Jacob Haqq-Misra in The Boston Globe

When Pope John Paul II announced in 1992 that Galileo was correct, more than 350 years after his condemnation by the Inquisition, the world reacted with apathy, relief, and amusement. No one doubts any more that Earth revolves around the sun, and even private Catholic schools had been teaching heliocentricity to their students prior to the official apology.

Our historical understanding of the Galileo affair tends to implicate the church as clinging unnecessarily to a literal interpretation of the Bible, which required the faithful to accept the untenable theory of geocentrism. From elementary school onward, we’re taught that the church stood firmly athwart scientific progress, bellowing “Stop!” Indeed, the clash has gone down through the ages as a sort of morality play of science versus religion, pitting the proponents of progress against religious reactionaries. But what if that morality play itself is nothing more than dogma?

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment