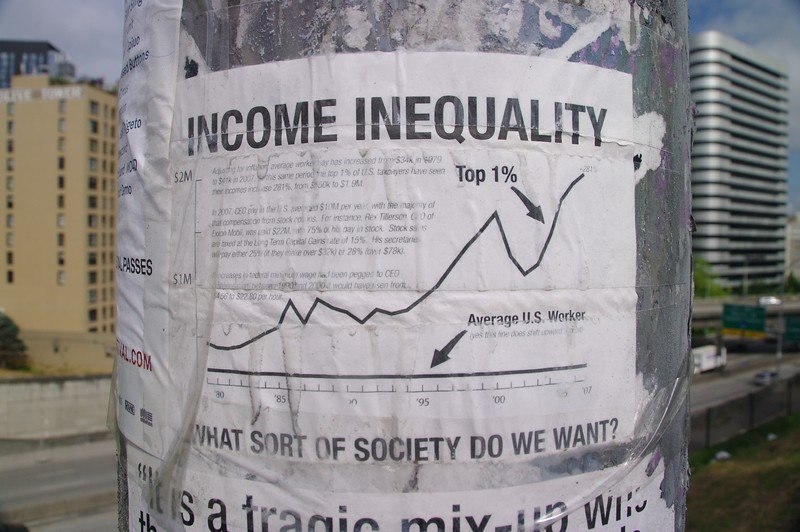

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

If absolute poverty is declining, while measures of relative inequality (of income or wealth) show a significant rise (or remain very high), this implies that the conditions of the poor may be improving, but those for the rich may be improving much more. But if people are less poor than before, should we be concerned about high or rising inequality, about how much better-off the rich are, and, if so, why? This is an important question on which more clarity is needed, as quite often when people tell you why they dislike inequality many of the examples they cite are really about their aversion to the stark poverty around them.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment