Some things have always been worth celebrating.

via the Big Think blog by Robby Berman

Stonehenge sunrise. Photo credit: Tony Craddock on Shutterstock

- Some lost ancient holidays aren't really so lost after all.

- All of us celebrate at least some pagan traditions whether we know it or not.

- There are two things that tend to bring humans together: crises and holidays.

==============================

via the New Statesman by Michael Prodger

Pierre Bonnard painted what he remembered not what he saw, and his enigmatic pictures are ripe with the immanence of decline.

Nude in the Bath (1936-38) by Pierre Bonnard

There is a strand of art that exists on the edge of the mainstream – existing, too, slightly out of time, regardless of when it was made. It takes as its subjects the domestic interior and silence and finds in them both poetry and melancholy. The greatest exponent of this intimism was Vermeer and other leading practitioners number Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916), and two 20th-century English painters, Howard Hodgkin and Patrick Caulfield. The most prolific though was Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947), who was the prime exponent of “slow” painting during a time of frenetic artistic change.

Continue reading about an exhibition that ended in May. It is still worth reading about the artist if you have no prior knowledge of him as I didn’t.

==============================

via the OUP blog by Matt Karush

Violin Strings by Providence Doucet. CC0 via Unsplash.

Despite their enthusiasm for borrowing from other fields and incorporating new types of source material, many historians remain reluctant to analyze music. For example, when the American Historical Association dedicated its 2015 Annual Meeting to “History and Other Disciplines,” organizers called for work that engaged with anthropology, material culture, archaeology, visual studies, and museum studies, but they were noticeably silent about music and musicology. What explains this aversion?

Continue reading

==============================

via About History

Initially, the settlements that emerged on the territory of the city were divided settlements, in which the community played the main role. In the VIII century B.C. a group of primitive settlements appeared in Latia, on the hills of Palatin, Esquilina, Ceelia and Quirinale. The fortified villages were tribal villages located on the tops and upper slopes of the hills. The marshy lowlands between them became habitable only with time, when people began to drain them. The inhabitants of the Palatine Hill burned their dead, like other Latin tribes, while on the Quirinal hill, the deceased were buried in the ground, in wooden decks. Therefore, it is believed that the Palatine and part of Celia belonged to the Latins, and the northern hills – to the Sabines. The first Roman settlers lived in round or rectangular huts, built on a wooden frame with clay plaster; their main occupation was cattle breeding. Not only hills, but also lowlands between them, were mastered for economic purposes.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

‘How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix’ begins with the wonderfully rhythmical lines ‘I sprang to the stirrup, and Joris, and he; / I gallop’d, Dirck gallop’d, we gallop’d all three’. This energetic Robert Browning poem describes a horse-ride to deliver some important news, although we never learn what the news actually is. Instead, the emphasis is on the journey itself, with the sound of the galloping horses excellently captured through the metre of the verse.

Continue reading

==============================

Arts & Letters Daily: Bob Blaisdell in the Los Angeles Review of Books

Tolstoy started writing Anna Karenina at the end of March 1873 and finished it in the summer of 1877. He complained about the labor and regularly defamed the novel during and after its composition. In the midst of serializing it at the highest rate a Russian author had ever been paid, Tolstoy wanted to kill himself. From the first drafts and sketches he knew Anna would commit suicide, but he didn’t know how he was going to prevent himself from drowning or shooting himself. In terms of hyperconscious despair, Tolstoy was one with his creation. In A Confession (begun in 1875, revised and completed in 1881), he describes himself looking into the chasm of depression; his head spinning, he was ready to plunge to the bottom, but an unusual (for him) lack of conviction held him back.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Big Think blog by Evan Fleischer

- Researchers appear to have found a neural basis for "cute aggression."

- Cute aggression is what happens when you say something like, 'It's so cute I want to crush it!'

- But it's also a complex response that likely serves to regulate strong emotions and allow caretaking of the young to occur.

==============================

via the OUP blog by Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis

“Music Melody” by MIH83. CC0 via Pixabay.

Music can intensify moments of elation and moments of despair. It can connect people and it can divide them. The prospect of psychologists turning their lens on music might give a person the heebie-jeebies, however, conjuring up an image of humorless people in white lab coats manipulating sequences of beeps and boops to make grand pronouncements about human musicality.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

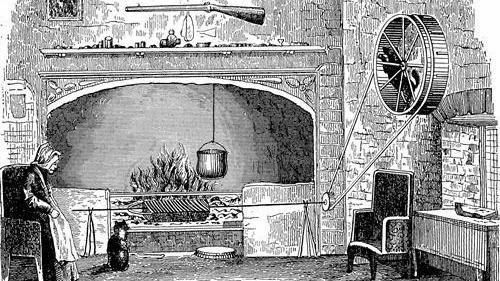

The Vernepator Cur was once a ubiquitous dog breed in the UK and the American colonies, and it had a job: for six days a week, it ran tirelessly in a wheel in the kitchen that was geared to turn a meat-spit over the fire (on Sundays it went to church with its owners and served as their foot-warmer).

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

We tend to associate nonsense verse with those great nineteenth-century practitioners, Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, forgetting that many of the best nursery rhymes are also classic examples of nonsense literature. ‘Hey Diddle Diddle’, with its bovine athletics and eloping cutlery and crockery, certainly qualifies as nonsense. What does this intriguing nursery rhyme mean, if anything? What are its origins? Iona and Peter Opie, in The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford Dictionary of Nusery Rhymes), call ‘Hey Diddle Diddle’ ‘probably the best-known nonsense verse in the language’, adding, ‘a considerable amount of nonsense has been written about it.’

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment