via 3 Quarks Daily: Ed Yong in The Atlantic

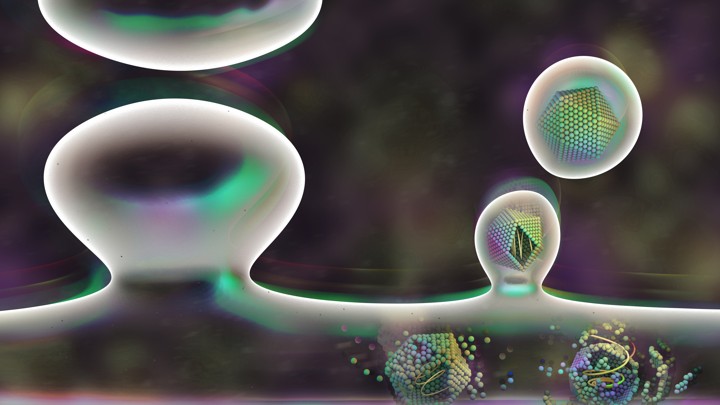

Virus-like shells budding off from one neuron and moving to another. CHRIS MANFRE

When Jason Shepherd first saw the structures under a microscope, he thought they looked like viruses. The problem was: he wasn’t studying viruses.

Shepherd studies a gene called Arc which is active in neurons, and plays a vital role in the brain. A mouse that’s born without Arc can’t learn or form new long-term memories. If it finds some cheese in a maze, it will have completely forgotten the right route the next day. “They can’t seem to respond or adapt to changes in their environment,” says Shepherd, who works at the University of Utah, and has been studying Arc for years. “Arc is really key to transducing the information from those experiences into changes in the brain.”

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle enjoys the once-popular but now largely forgotten detective stories of Ernest Bramah

The name Ernest Bramah may be largely forgotten now, but he created a detective whose popularity rivalled that of Sherlock Holmes (at least so it is rather improbably claimed). Bramah (1868-1942) created Max Carrados, a popular sleuth whose adventures appeared in The Strand magazine, which also published Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. But there is one important difference between Max Carrados and Sherlock Holmes: Carrados is blind.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Guardian by Rebecca Rideal

Genghis Khan was not just a brutal warlord.

Photograph: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

You wait years for a historical theory to be debunked and then three come around at once. So far this week [in January 2018], we have been told that the mysterious pestilence that wiped out 15 million Aztecs between 1545 and 1550 was not smallpox or measles, but enteric fever, that the Black Death was spread by fleas and lice from humans as well as rat fleas (a theory that, in truth, has been around for a while), and that the supposed origins of the phrase “whipping boy” (where surrogates were punished in place of young royals) seem to be false. In the spirit of debunking myths, here is my (in no way exhaustive) list of 10 historical “mythconceptions”.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Rob Beschizza

One of the few permitted vices in Nineteen Eighty-Four is Victory Gin, which oils the outer party and offers suggestions of Englishness and party power: it's always served with clove bitters, implying that Oceania's boots are on the ground in Asia. Chemistry professor Shirley Lin wrote an interesting post about gin's place in Orwell's dystopia.

Continue reading

==============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Daisy Dunn in the TLS

Modigliani would be out drinking in Paris when a sudden desire came over him to remove his clothes, flex his naked body, and give a performance of Dante’s Divine Comedy. If it wasn’t Dante then it was something else – he could recite dozens of poems from memory, even while drunk, a skill that served him particularly well when he met the young Russian poet Anna Akhmatova in 1910 and determined to win her heart. She was on her honeymoon at the time but Modigliani was undeterred. They soon began an affair, absconding to the Jardin du Luxembourg to sit in the rain and intone the poetry of Verlaine. “We rejoiced that we both remembered the same work of his”, Akhmatova recalled later.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

The best poems of Wilfred Owen

Previously, we’ve selected ten of the best poems about the First World War; but of all the English poets to write about that conflict, one name towers above the rest: Wilfred Owen (1893-1918). Here’s our pick of Wilfred Owen’s ten best poems.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Big Think blog by Robby Berman

Propofol does more than knock a patient out — it blocks neural connections.

To fully understand how anesthesia works on human consciousness, we’d have to first understand exactly how consciousness works. So that’s a problem. The most frequently used anesthesia is propofol, which knocks out patents quickly and smoothly and prevents them from feeling pain during surgery. But exactly how propofol and other anesthetics do what they do has been unknown. “It is indeed a 180-year-old question, one of the unresolved mysteries in medicine, Bruno van Swinderen tells ScienceAlert van Swinderen is the senior author of a new study that suggests a possible solution: Propofol disrupts communication between neurons. It shuts off thinking while you sleep.

Continue reading [Note: the article starts with a picture of a canula in the back of someone's hand.]

==============================

via the Guardian by Susannah Lydon

Detail of a fungal mycelium Photograph: Alamy

Fossil fungi from over 400m years ago have altered our understanding of early life on land and climate change over deep time

Much of the weirdness depicted in the TV show Stranger Things is distinctly fungal. The massive organic underground network, the floating spores, and even the rotting pumpkin fields all capture the “otherness” of fungi: neither plants nor animals, often bizarre-looking, and associated with decay. As weird as they may seem to us, fungi are integral to the story of the evolution of our landscapes and climate.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Clive Thompson

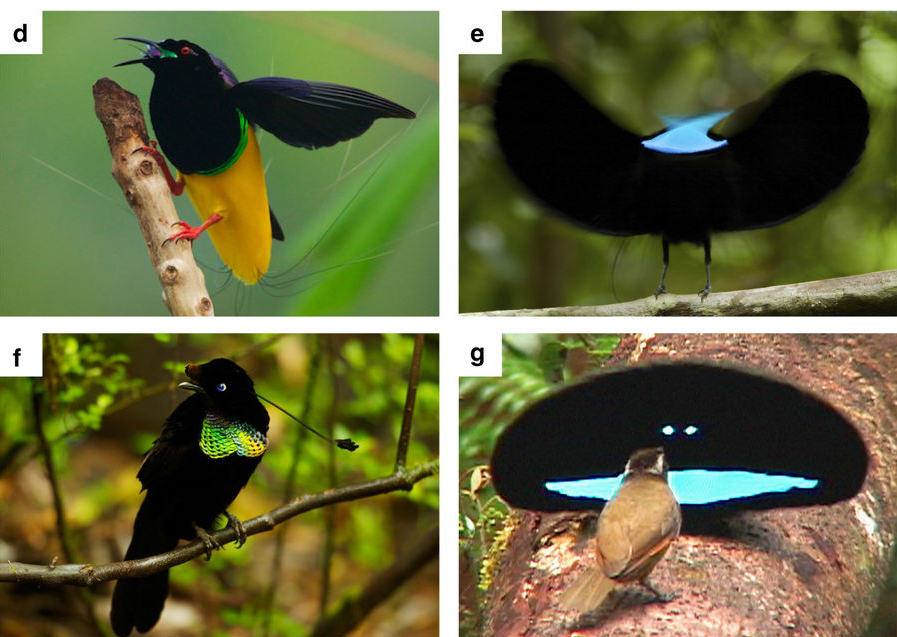

How are the feathers of Papua New Guinea's "birds of paradise" so freakishly black?

Because, man, they really are. Crows and blackbirds look, y'know, black-like ... but birds of paradise look like a hole has been punched in reality. It's like they've been coated in Vantablack, the freakily engineered substance you can coat on objects to make them superdark. The birds also often have striking colors, of course; but the parts of them that are black are inkily so.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

A reading of a poem by America’s first poet

Anne Bradstreet (1612-1678) was the first person in America, male or female, to have a volume of poems published. She’d been born in England, but was among a group of early English settlers in Massachusetts in the 1630s. In 1650, a collection of her poems, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America, was published in England, bringing her fame and recognition. This volume was the first book of poems by an author living in America to be published. She continued to write poetry in the ensuing decades. In ‘The Author to Her Book’, one of Bradstreet’s most widely studied and analysed poems, she addresses The Tenth Muse.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment