via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

Collectors Weekly’s feature on “headbages” tells the story of the 1000+ badge collection of bike-mechanic-turned-evolutionary-biologist Jeffrey Conner, who published a book on the subject, featuring an alphabetic index of photos from his collection.

Continue reading

=============================

via AbeBooks by Jessica Doyle

Defining a cult book is not easy. Let’s start with the more obvious aspects of cult lit. To begin, a cult book should have a passionate following. Buckets of books fall into this category, including classics like J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and On the Road by Jack Kerouac. But even mega sellers Harry Potter and 50 Shades of Grey can be considered cult lit by that definition. A cult book should have the ability to alter a reader’s life or influence great change, and for the purpose of this list, it should also be a bit odd and a tad obscure.

Many of the titles we’ve selected have barely seen the light of day beyond their incredibly dedicated and perhaps obsessive following. Only five copies of Leon Genonceaux’s 1891 novel The Tutu existed until the 1990s because Genonceaux was already in trouble with French police for immoral publishing when he wrote it and feared a life in prison if he distributed the book to the public. Similarly, The Red Book by Carl Jung was reserved for Jung’s heirs for decades before it was made available to a wider audience.

Some of the books on our list are more widely known (though not necessarily widely understood). Robert M. Pirsig introduced the Metaphysics of Quality, his own theory of reality, in his philosophical novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. The book was rejected by over 100 publishers before it was finally published by William Morrow & Company in 1974 and today it’s regarded as one the most influential texts in American culture.

From funny fiction and serious science fiction to knitting manuals and alternative art, the books on this list have steered the course of an individual’s life, created a wave of change in a society, culture, or generation, and garnered fanatic attention from a few or few million readers for their quirky and obscure content.

Continue reading

=============================

The Greek colour experience was made of movement and shimmer. Can we ever glimpse what they saw when gazing out to sea?

via Arts & Letters Daily: Maria Michela Sassi in AEON

Homer used two adjectives to describe aspects of the colour blue: kuaneos, to denote a dark shade of blue merging into black; and glaukos, to describe a sort of ‘blue-grey’, notably used in Athena’s epithet glaukopis, her ‘grey-gleaming eyes’. He describes the sky as big, starry, or of iron or bronze (because of its solid fixity). The tints of a rough sea range from ‘whitish’ (polios) and ‘blue-grey’ (glaukos) to deep blue and almost black (kuaneos, melas). The sea in its calm expanse is said to be ‘pansy-like’ (ioeides), ‘wine-like’ (oinops), or purple (porphureos). But whether sea or sky, it is never just ‘blue’. In fact, within the entirety of ancient Greek literature you cannot find a single pure blue sea or sky.

Continue reading

=============================

via Boing Boing by Mark Frauenfelder

I always hate having to write “Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell”, because it's such a wtf mouthful. But they make beautiful animated explainer videos, so I have to write “Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell” a lot. They are always great, but this 6-minute guide to thinking your way out of existential dread might be their best video yet. The graphics are stupendous.

Continue reading

=============================

via the Guardian by Carlo Rovelli

How does a book about theoretical physics sell more than 1m copies? Rovelli explains how he set about sharing his wonder at quantum science

‘The book is my dream of getting across the intense magic of my trade’ … Carlo Rovelli on Italian TV. Photograph: Pier Marco Tacca/Getty

There are two kinds of popular science books. The first kind is for passionate readers. Say you are mad about butterflies. You want a book that gives you all the details about all varieties of butterflies, their lives, habits and colours. You are keen to know everything.

The other kind of popular science book is written for everybody else. Say you never cared much for butterflies, but one day you happened on a book filled with incredible images of their phantasmagorical wings and read an interesting fact, such as how many of them live only for a single day … even though you don’t want many details, you suddenly find yourself wanting to learn more.

Continue reading

=============================

via Boing Boing by Rusty Blazenhoff

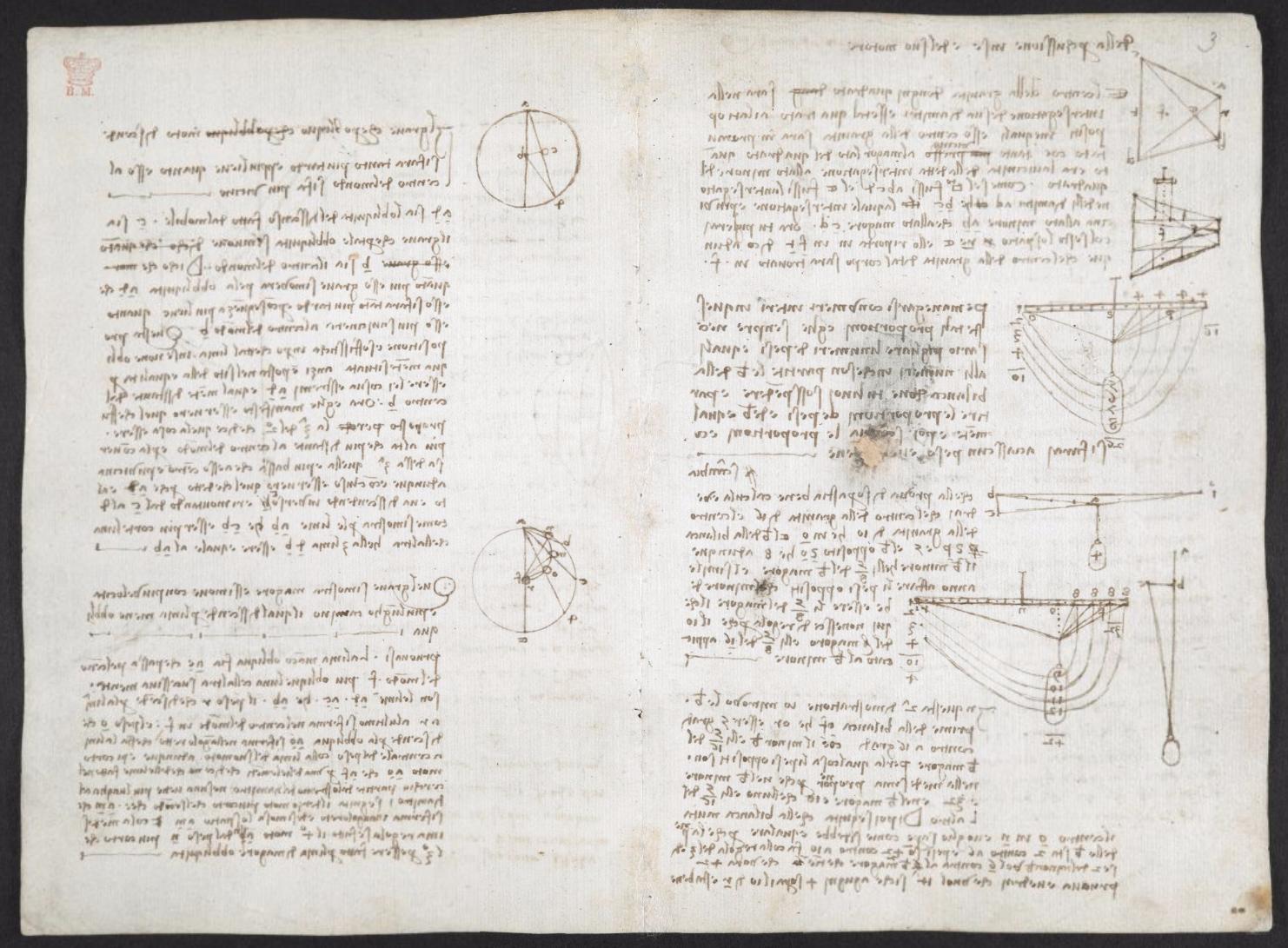

The British Library has digitized 570 loose pages of notes written and drawn by Leonard da Vinci to compile a notebook which is called, The Codex Arundel.

You can view the document online for free, although it’s written in Italian and uses his “characteristic left-handed mirror-writing (reading from right to left)”.

Continue reading

=============================

via Big Think by Paul Ratner

Bubble Chamber Baltay Experiment. Credit: Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

Quantum mechanics continues to provide brain-busting discoveries as mathematicians find that quantum mechanical particles can move in the opposite direction of where they are being pushed. That’s like pushing a ball forward and having it roll back towards you instead.

Scientists at Universities of York, Munich and Cardiff showed that on microscopic levels, quantum particles can travel in reverse of their momentum, exhibiting a special property called “backflow”.

Researchers were aware of such movement previously but in free” quantum particles that don’t have any force acting on them. By using analysis and numerical methods, they found that backflow is always there, but as a small hard-to-measure effect.

What’s responsible for this surprising property? Wave-particle duality, which holds that every particle may behave as a particle or a wave, and the “probabilistic nature” of quantum mechanics where particle properties are not fixated until observed.

Continue reading

=============================

via Interesting Literature

A commentary on Donne’s great poem of farewell

One of the great ‘goodbye’ poems in the English language, ‘A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning’ is, in a sense, not a farewell poem at all, since Donne’s speaker reassures his addressee that their parting is no ‘goodbye’, not really. The occasion of the poem was a real one – at least according to Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler and friend of Donne’s, who recorded that Donne wrote ‘A Valediction’ for his wife when he went to the Continent in 1611.

Continue reading

=============================

via OUP Blog by Kim Vollrodt

“Stamp – inked from Folger Shakespeare Library” uploaded by POP,CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

In Shakespeare’s England, the term “friend” could be used to express a wide range of interpersonal relations. A friend could be anything from a neighbour, a lover, or fellow countryman, to a family member or the close personal acquaintance we understand as a “friend” today. Much like power or love, different types of friendship are one of the central themes in Shakespeare’s plays, dealing with the positivity of close and trusting friendships, but also with its fragility and the resultant dangers when trust breaks down.

Being a true Shakespearean friend means above all loyalty, unwavering support, and mutual respect – clearly shown in the relationship between Hamlet and Horatio. Horatio is Hamlet’s one true ally and stands by the tragic Prince throughout his troubles, going so far as to offer to commit suicide for him. This tragic conclusion seems to be a pattern for many Shakespearean friends, revealing the darker side of human relationships. Some of the most famous villains are the ones who betray their nearest and dearest friends, indicating that unwavering trust and friendship, like the trust Julius Caesar places in his friend Brutus until the very end, can be easily misplaced.

Continue reading

=============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: John McCumber in Aeon

The chancellor of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was worried. It was May 1954, and UCLA had been independent of Berkeley for just two years. Now its Office of Public Information had learned that the Hearst-owned Los Angeles Examiner was preparing one or more articles on communist infiltration at the university. The news was hardly surprising. UCLA, sometimes called the ‘little Red schoolhouse in Westwood’, was considered to be a prime example of communist infiltration of universities in the United States; an article in The Saturday Evening Post in October 1950 had identified it as providing ‘a case history of what has been done at many schools’.

The chancellor, Raymond B Allen, scheduled an interview with a ‘Mr Carrington’ – apparently Richard A Carrington, the paper’s publisher – and solicited some talking points from Andrew Hamilton of the Information Office. They included the following: ‘Through the cooperation of our police department, our faculty and our student body, we have always defeated such [subversive] attempts. We have done this quietly and without fanfare – but most effectively.’ Whether Allen actually used these words or not, his strategy worked. Scribbled on Hamilton’s talking points, in Allen’s handwriting, are the jubilant words ‘All is OK – will tell you.’

Allen’s victory ultimately did him little good. Unlike other UCLA administrators, he is nowhere commemorated on the Westwood campus, having suddenly left office in 1959, after seven years in his post, just ahead of a football scandal. The fact remains that he was UCLA’s first chancellor, the premier academic Red hunter of the Joseph McCarthy era – and one of the most important US philosophers of the mid-20th century.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment