via the Guardian by Ian Sample, science editor

Environmental crisis clouding scientific objectivity about plants’ feelings, says botanist

The plant neurobiology debate is shaping up to be the biggest botanical bunfight since the Romantic era.

Photograph: Alamy

The gardening gloves are off. Frustrated by more than a decade of research which claims to reveal intentions, feelings and even consciousness in plants, more traditionally minded botanists have finally snapped. Plants, they protest, are emphatically not conscious.

The latest salvo in the plant consciousness wars has been fired by US, British and German biologists who argue that practitioners of “plant neurobiology” have become carried away with the admittedly impressive abilities of plants to sense and react to their environments.

Continue reading

==============================

via Ancient Origins by Ed Whelan

Peel Castle, Isle of Man. Source: vulcan57 / Adobe

The Isle of Man is a small island in the Irish Sea between Ireland and England and is a Crown Dependency of the United Kingdom. Because the island was settled approximately 8000 years ago, it has a long, diverse history and fascinating archaeological sites. A unique Celtic culture evolved alongside the local language, Manx, which is related to Gaelic Irish and Scottish. One of the most interesting sites on the Isle of Man is Peel Castle, which was built by the Vikings.

Continue reading

==============================

via The New York Review of Books by Daniel Mendelsohn

- The Best Intentions

by Ingmar Bergman, translated from the Swedish by Joan Tate

Arcade, 298 pp., $16.99 (paper) - Sunday’s Childrenby Ingmar Bergman, translated from the Swedish by Joan Tate

Arcade, 153 pp., $14.95 (paper) - Private Confessionsby Ingmar Bergman, translated from the Swedish by Joan Tate

Arcade, 160 pp., $16.99 (paper)

Ingmar Bergman on the set of Fanny and Alexander, from the 1984 documentary The Making of Fanny and Alexander

Toward the beginning of Ingmar Bergman’s autobiographical film Fanny and Alexander, a beautiful young boy wanders into a beautiful room. The room is located in a rambling Uppsala apartment belonging to the boy’s widowed grandmother, Helena Ekdahl, once a famous actress and now the matriarch of a spirited and noisy theater family. As the camera follows the boy, Alexander, we note the elaborate fin-de-siècle decor, the draperies with their elaborate swags, the rich upholstery and carpets, the pictures crowding the walls, all imbued with the warm colors that, throughout the first part of the film, symbolize the Ekdahls’ warm (when not overheated) emotional lives. Later, after the death of Alexander’s kind-hearted father, Oscar, who is the lead actor of the family troupe, his widow rather inexplicably marries a stern bishop into whose bleak residence she and her children must move. At this point, the film’s visual palette will be leached of color and life; everything will be gray, black, coldly white.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

Sunday morning is a great time to sit back, relax, and read a bit of poetry. And below we’ve gathered together six of the finest poems about Sunday: you might consider this poetry’s ‘Sunday best’. From meditations on prayer and church to staying at home and pondering the bigger questions of life, these six classic Sunday poems are ideal Sunday reading.

Continue reading

==============================

a post by Joyce C. Havstad

“Migratory birds” by Myriams-Fotos via Pixabay

We used to think – and many of us were taught in school – that the dinosaurs went extinct many millions of years ago. But now it seems like this might not be the case. Today’s biologists tend to think birds are dinosaurs, which means that, if true, the dinosaurs did not go entirely extinct after all. Some of them survived.

Scientific ideas can change over time – just as scientific ideas about birds, dinosaurs and extinction have changed over time. Change like this means scientific experts can be wrong, and it also means they can disagree with one another. If scientists today think birds are dinosaurs, then current scientists think past scientists were wrong.

Continue reading

==============================

via Ancient History by Martin Sweatman

Taurid meteor shower 13,000 years ago. Source: IgorZh / Adobe .

Around 13,000 years ago, the Earth burned. A swarm of comet debris from the Taurid meteor stream had blasted the Americas and parts of Europe; the worst day in prehistory since the end of the ice age. Many species of large animal were exterminated by the conflagration and ensuing cataclysms. And those that survived the initial onslaught could do little against the floods, acid rain, and starvation that followed.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Rob Beschizza

How do you know for sure if your carefully-recreated 18th-century paint would fool pass muster as art dealers a legitimate recreation long enough to get away with it? of the authentic originals? Tom Scott visits the Forbes Pigment Collection.

The Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums is a collection of pigments, binders, and other art materials for researchers to use as standards: so they can tell originals from restorations from forgeries. It's not open to the public, because it's a working research library – and because some of the pigments in there are rare, historic, or really shouldn't be handled by anyone untrained

==============================

via The National Archives Blog by Claire Kennan

On 19 June 1829, Sir Robert Peel’s Act for Improving the Police in and near the Metropolis received royal assent. Peel argued that there was a real need for the establishment of a new police force stating that:

"It is the duty of Parliament to afford the inhabitants of the Metropolis and its vicinity, the full and complete protection of the law and to take prompt and decisive measures to check the increase of crime, which is now proceeding at a frighteningly rapid pace."

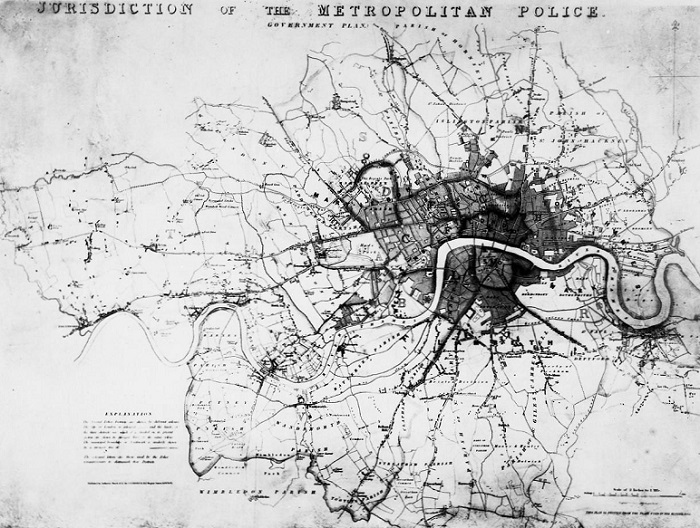

Map of Jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police, 1837. Catalogue reference: MEPO 13/326

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle reviews Stephen Coote’s English Literature of the Middle Ages

Stephen Coote’s English Literature of the Middle Ages (Pelican) was published thirty years ago, in 1988. It’s taken me until this week to read it, but it’s one of the most illuminating and important introductions to medieval English literature you could hope to find. Clear, accessible, and endlessly informative, Coote’s book covers everything from Beowulf to the Morte Darthur, taking in alliterative and rhyming verse, courtly dream-visions and Arthurian narratives, Anglo-Saxon kennings and Middle English prose.

Continue reading

And I simply had to look up “kennings” – a word I did not recognise.

Here you go

No comments:

Post a Comment