via the OUP blog by Robyn Arianrhod

Night sky in Hatchers Pass, Alaska. Photo by McKayla Crump. CC0 via Unsplash

The enigmatic Elizabethan Thomas Harriot never published his scientific work, so it’s no wonder that few people have heard of him. His manuscripts were lost for centuries, and it’s only in the past few decades that scholars have managed to trawl through the thousands of quill-penned pages he left behind. What they found is astonishing – a glimpse into one of the best scientific minds of his day, at a time when modern science was struggling to emerge from its medieval cocoon.

Continue reading

==============================

via The National Archives Blog by Neil Cobbett

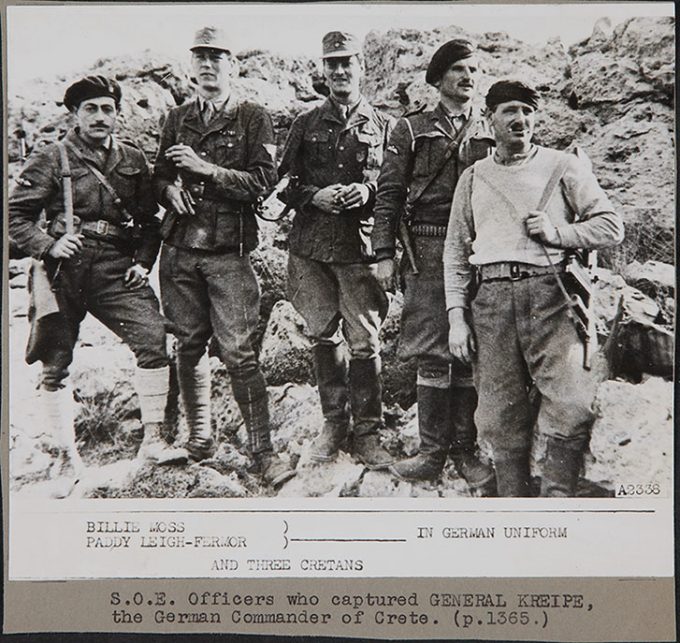

SOE Mid East-Balkans April-Dec 1944 Capturers of Gen Kreipe – Crete.

Catalogue reference: HS 7/273

The methods used by Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents to pass as members of the local population in Nazi-held territory were carefully thought out; they were never used lightly or over-egged, and required subtlety and understatement. Disguises or camouflage were used in a number of cases but there were alternative means by which SOE agents managed to ‘pass’ as locals in the area they operated, or in the identities they had assumed.

The incidence of cases where agents needed to use disguises was thus relatively small. Disguises were usually adopted where an agent had to return to the place where they had been active, after narrow escapes from Axis personnel and where their identity had become known.

Continue reading

==============================

via Ancient Origins by Charles Christian

Hecate: Procession to a Witches' Sabbath by Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652) (Public Domain)

During the Early Modern period of European history – from the Renaissance (1500) to the French Revolution (1800), hundreds of thousands of witches suffered the terrible fate of being burned at the stake for their beliefs during the so-called ‘Burning Times’. Modern estimates suggest a revised figure of between 40,000 to 50,000 over a period of 300 years, however, following my own researches into witchcraft trials in England , it would appear the reality was far less dramatic, albeit not for the individuals convicted of witchcraft!

Continue reading

==============================

via the Guardian by Ian Sample, science editor

Huge thigh bone in Crimean cave belonged to largest bird found in northern hemisphere

An artist’s impression of the giant bird whose remains were found in a Crimean cave. Photograph: Andrey Atuchin

Giant flightless birds that dwarfed modern ostriches and weighed nearly half a tonne roamed Europe when the first archaic humans arrived from Africa, scientists say.

Researchers unearthed the fossilised thigh bone of one of the feathered beasts while excavating a cave on the Crimean peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea. It is the first time such a massive bird has been found in the northern hemisphere.

Continue reading

==============================

via ResearchBuzz Firehose: University of Wurzburg in EurekAlert

To explore the Egyptian temple economy through a particular genre of sources: This is the aim of the DimeData research project. The project is led by Professor Martin Andreas Stadler, holder of the Chair of Egyptology; Dr. Maren Schentuleit, research assistant to the Chair, will be responsible for the concrete work.

Credit: Gunnar Bartsch / Universität Würzburg

Imagine archaeologists working 2,000 years from now to decipher the account statements of a large commercial enterprise that ended up in the bin in 2018 and have been forgotten since. The majority of these notes are in a deplorable condition: eaten by mice, glued together, torn and fragmentary, and written in a strange script that cannot be found in any other place. What makes the work even more difficult is that the individual scraps of paper are not neatly collected in one place, but are distributed across many museums and libraries in Europe. Which is why, for example, no one has yet noticed that the upper half of a rather unfortunate note is in Vienna, while the lower half is in Berlin.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle reads a classic story of alien possession by the master of British science fiction

What if your son had an imaginary friend with whom he often conversed, answering questions that nobody had apparently asked, and behaving as though this invisible and seemingly immaterial Other were the most natural thing in the world? Many parents will probably have observed such a thing with their own children. But what, then, if the idea started to take root, a small but nevertheless nagging doubt, that this imaginary friend was not imaginary at all, but something objectively real, which had inhabited your child’s brain and was capable of speaking directly to him through some form of thought-transference?

Continue reading

==============================

via the OUP blog by Christopher Cannon

Church Dom Chapel by Tama66. Public Domain via Pixabay.

We have long assumed that medieval sermons were written for the laity, that is, those with no Latin and probably minimal literacy. But most of the sermons that survive in English contain a significant amount of Latin. What did a medieval lay person understand when he or she heard a sermon?

The function of such Latin is just one part of the blurry picture we have of the nature of medieval literacy. Walter Map (1140-1210) described a boy he knew whose family was clearly of some means (the boy later became a knight) who was, on the one hand, illiteratus, but on the other hand was praised for his penmanship because he “knew how to transcribe any series of letters whatever.” Margery Kempe says in the book she wrote, by dictating her words to a priest, that she is “not lettryd,” but that book describes how she was hit on the head by masonry in a church while she has “hir boke in hir hand,” and her book itself contains Latin quotations she should not have been able to understand.

Continue reading

==============================

via Ancient Origins by DHWTY

Source: grandfailure / Adobe Stock

Black Caesar was a notorious pirate who lived between the 17 th and 18 th centuries. Originally from West Africa , Black Caesar was captured and sold into slavery. The ship he was in, however, sank off the coast of Florida but Black Caesar survived, and began his career in piracy, eventually rising to notoriety. Eventually, Black Caesar’s reign of terror came to an end in 1718, when he was convicted for piracy and executed.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Jason Weisberger

Prior to its recent discovery the baris was a ship best known through "the father of history," Herodotus' description. There were other references in literature but no physical sign this type of craft ever truly existed. A recent discovery shows Herodotus was no liar.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle reads the rich and rewarding planetary romances of a forgotten pulp writer

What happens if you cross the Martian adventures of Edgar Rice Burroughs with the pulp fantasy of Robert E. Howard? You get the planetary fantasies of Leigh Brackett, the underrated writer of ‘science fantasy’ who penned a number of hugely entertaining short stories and novellas set on Venus and Mars. Leigh Brackett hasn’t quite been forgotten, at least by those (including the fantasy and SF author Michael Moorcock) who have championed her work and, in the case of Moorcock among others, been inspired by her: Moorcock himself wrote a trilogy of Martian novels, Kane of Old Mars, which were influenced by Burroughs but also, I suspect, by Brackett. (Leigh Brackett also inspired, and later collaborated with, a young Ray Bradbury: one of their co-authored stories, ‘Lorelei of the Red Mist’, is included in the edition I mention and review below.) But nor has she ever quite got her due. Like another queen of the golden age of pulp fantasy, C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett has been allowed to fall out of print. Much of Brackett’s best writing goes unacknowledged: she also worked with Jules Furthman and William Faulkner on the critically acclaimed screenplay for the 1946 film version of Raymond Chandler’s novel, The Big Sleep, one of the classics of the noir genre.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment