Vincente Minnelli’s daring MGM musical starred the 17-year-old Leslie Caron, had a staggeringly ambitious ballet sequence and became a surprise Oscar winner. Now it’s become a Tony-winning smash in London

via the Guardian by Sarah Crompton

Joie de vivre … An American in Paris at the Dominion theatre, London. Photograph: Tristram Kenton for the Guardian

When Vincente Minnelli and Gene Kelly were making the 1951 film An American in Paris, their schedule had to be tailored to the needs of their star, Leslie Caron. The 17-year-old, who had been spotted by Kelly dancing with the Ballets des Champs-Élysées in Paris when he was on holiday two years previously, had been so weakened by wartime malnutrition that she could only work on alternate days.

Continue reading

=============================

via Boing Boing by Mark Frauenfelder

Bobby Kasthuri is a neuroscientist at Argonne National Laboratory. In the video he was asked to explain what a connectome is to 5 different people; a 5 year-old, a 13 year-old, a college student, a neuroscience grad student and a connectome entrepreneur.

Continue reading and viewing

=============================

via Interesting Literature

Love and death are perhaps the two most popular and perennial subjects for poetry, and many poets have attempted to put our thoughts about mortality into words that burn, in Thomas Gray’s memorable phrase. So choosing just ten definitive poems about death is going to prove tricky. We’ve attempted to make the task a little easier in this post by limiting ourselves to very short poems – none of the ten poems that follow is longer than ten lines, and many are somewhat shorter. We hope you enjoy this pick of the greatest short poems about death. [Information about who “we” is can be found here]

Continue reading

=============================

via OUP Blog by David Bevington

Page from original printing of Marlowe’s The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, 1628. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Christopher Marlowe was born in February of 1564, the same year as Shakespeare. He was the son of a Canterbury shoemaker, and attended the King’s School there. With fellowship support endowed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, young Marlowe matriculated at Corpus Christi College in Cambridge University in 1580 and received the BA degree in 1584. He may have served Queen Elizabeth’s government in some covert capacity, perhaps as a secret agent in the intelligence service presided over by Sir Francis Walsingham. He may have been recruited to this service during his stay at Cambridge. In 1597, the Privy Council ordered the university to award Marlowe the MA degree, refusing to credit the rumour that had intended to study at the English College at Rheims, presumably on order to prepare for ordination as a Roman Catholic priest. He spent lavishly on food and drink while at Cambridge to the extent that his fellowship would presumably not have afforded. He was absent for prolonged periods during his stay at the university. By 1587 he appears to have moved to London. Part I of Tamburlaine the Great, first performed in that year, took London by storm.

Continue reading

=============================

via the Guardian by Candice Pires

Judith Kerr’s home hasn’t changed since she featured it in her classic children’s book. Here, she talks about her favourite furniture, her family, and why she’s still working at 93

Judith Kerr in her kitchen in south-west London. ‘In 1962, Barnes was very grotty.’

Photograph: Suki Dhanda for the Guardian

You’ve probably already read – possibly countless times – about walking through the front door. Step into the hallway of Judith Kerr’s house, and you are following in the pawprints of the protagonist of her classic 1968 children’s book, The Tiger Who Came To Tea, which has never been out of print. Sit at the breakfast table in her kitchen, and you’ll see that and the white and yellow units are the same as those that surround Sophie and her mother as a surprise feline guest eats and drinks everything in sight.

Continue reading

=============================

via The National Archives blog by Dr Juliette Desplat

Arabic. Beautiful, poetic, terribly useful, and awfully difficult to learn. In the 1940s, the British Army must have shared my opinion: they set up a special school to teach Arabic to academically inclined young officers.

Continue reading

=============================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Alan Burdick in Nautilus

In a study published in 2011, Sylvie Droit-Volet, a neuropsychologist at Université Blaise Pascal, in Clermont-Ferrand, France, and three co-authors showed images of the two ballerinas to a group of volunteers. The experiment was what’s known as a bisection task. First, on a computer screen, each subject was shown a neutral image lasting either 0.4 seconds or 1.6 seconds; through repeated showings, the subjects were trained to recognize those two intervals of time, to get a feel for what each is like. Then one or the other ballerina image appeared onscreen for some duration in between those two intervals; after each viewing, the subject pressed a key to indicate whether the duration of the ballerina felt more like the short interval or the long one. The results were consistent: the ballerina en arabesque, the more dynamic of the two figures, seemed to last longer on screen than it actually did.

Continue reading

=============================

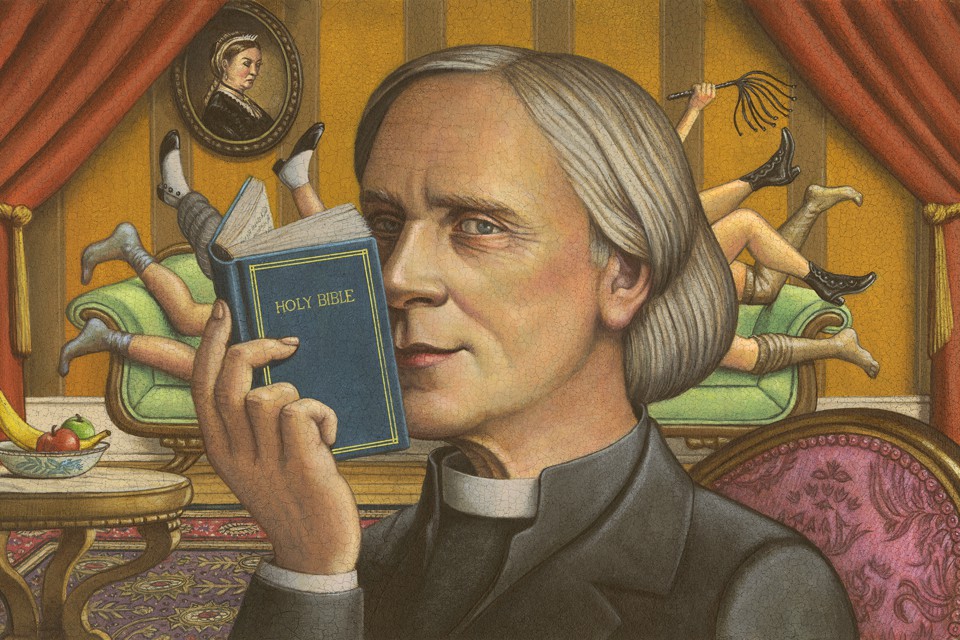

The discreet, disorienting passions of the Victorian era

via Arts & Letters Daily: Deborah Cohen in The Atlantic

Even by the formidable standards of eminent Victorian families, the Bensons were an intimidating lot. Edward Benson, the family’s patriarch, had vaulted up the clerical hierarchy, awing superiors with his ferocious work habits and cowing subordinates with his reforming zeal. Queen Victoria appointed him the archbishop of Canterbury, the head of the Anglican Church, in 1883. Edward’s wife, Minnie, was to all appearances a perfect match. Tender where he was severe, she was a warmhearted hostess renowned for her conversation. Most important, she was Edward’s equal in religious devotion. As a friend daringly pronounced, Minnie was “as good as God and as clever as the Devil.”

Continue reading

=============================

via Boing Boing by David Pescovitz

This week [of 28th February 2017] marks the 100th anniversary of the first jazz record ever released, or rather "jass" record. In a New York City recording studio, five white musicians called the Original Dixieland Jass Band recorded the "Livery Stable Blues" backed by the "Dixie Jass One-Step" on a 78 RPM disc. Of course, jazz music was actually "invented" primarily by black musicians in New Orleans as an evolution from ragtime in the 1910s. (But rather than recognize this long musical thread, Original Dixieland Jass Band leader/cornetist Nick LaRocca went on to make racist comments insisting he invented jazz.)

Continue reading and listening

=============================

Kay Redfield Jamison puts Robert Lowell on the couch in an exhilarating biography

via Arts & Letters Daily: Michael Dirda in The Washington Post

There are no half measures to Kay Redfield Jamison’s medico-biographical study of poet Robert Lowell. It is impassioned, intellectually thrilling and often beautifully written, despite being repetitive and overlong: A little too much would seem to be just enough for Jamison.

Nonetheless, “Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire” achieves a magnificence and intensity – dare one say a manic brilliance? – that sets it apart from more temperate and orderly biographies. Above all, the book demands that readers seriously engage with its arguments, while also prodding them to reexamine their own beliefs about art, madness and moral responsibility. Reading this analysis of “genius, mania, and character” is an exhilarating experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment