via the Guardian

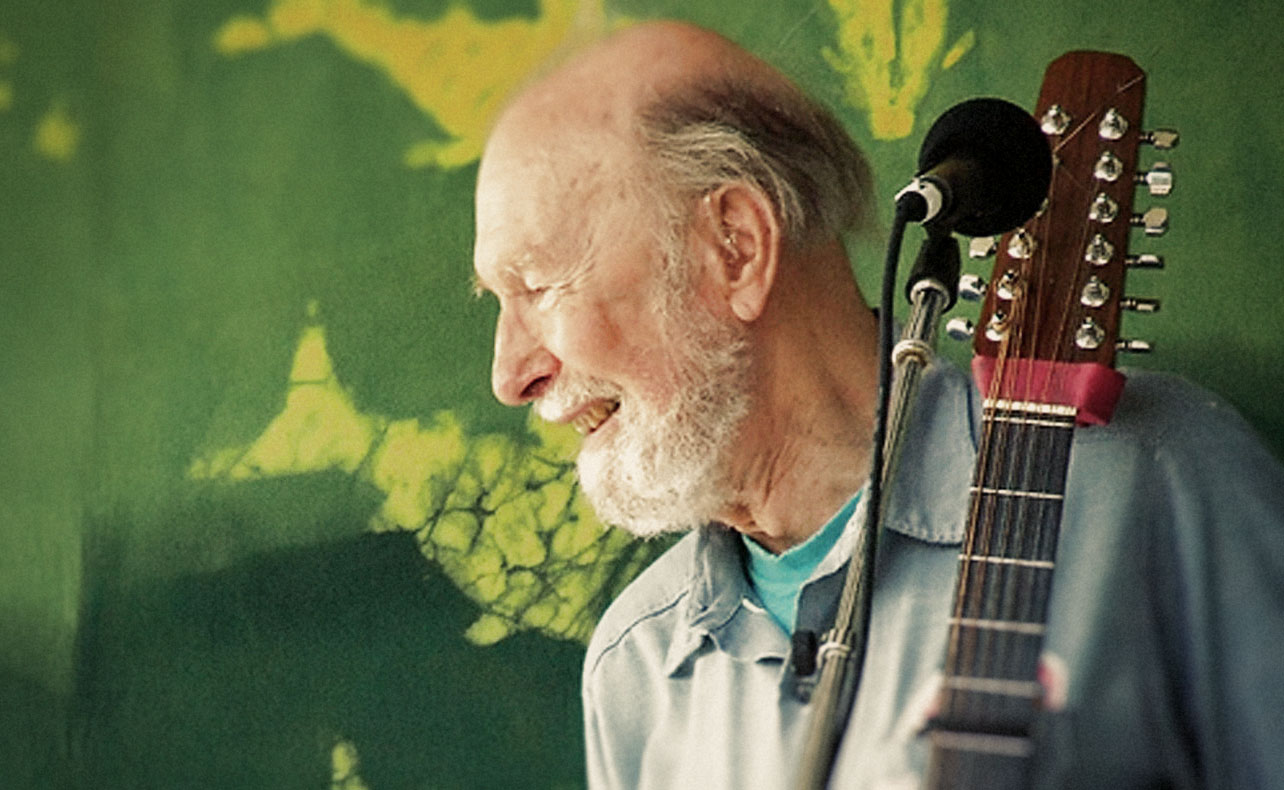

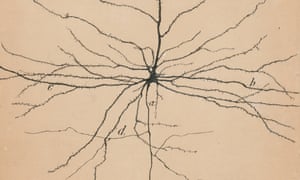

The 19th-century Spanish scientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience, was one of the first people to unravel the mysteries of the structure of the brain – and he made stunning drawings to describe and explain his discoveries.

Continue reading

===================================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Kishwar Rizvi in the Washington Post

At prayer in the mosque, Damascus, Syria. April 27, 1908.

Stereograph. (Library of Congress)

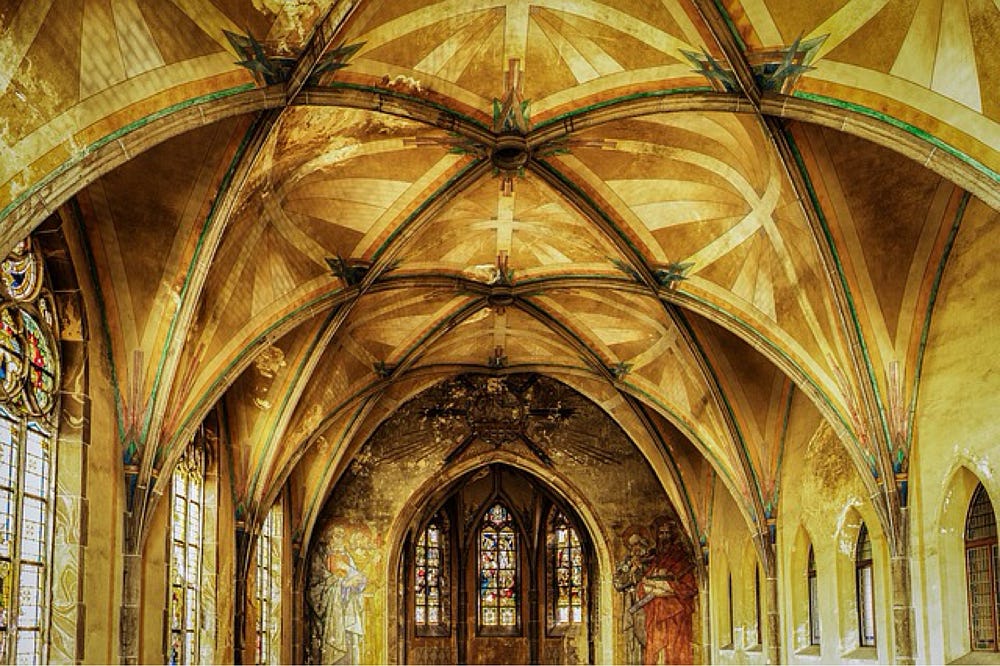

Every year, I take the students from my Islamic architecture course to visit the Islamic art collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York so they can see the cultural artifacts we’ve discussed in class. In 2013, we stopped to look at an aerial photograph of the 9th-century Great Mosque of Samarra, taken by the British Royal Air Force 100 years ago. The black-and-white image shows the vast scale of the mosque, renowned for having one of the tallest minarets in the world, at approximately 170 feet.

Someone remarked, “Wasn’t this the minaret that was installed with American snipers fighting Iraqi rebels in 2005, and blown up later?” Silence dropped over the group, and we moved on.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Futility Closet

In 1919 a bizarre catastrophe struck Boston's North End: A giant storage tank failed, releasing 2 million gallons of molasses into a crowded business district at the height of a January workday. In this week's episode of the Futility Closet podcast we'll tell the story of the Boston Molasses Disaster, which claimed 21 lives and inscribed a sticky page into the city's history books.

Continue reading

This would be funny except for the loss of life and livelihoods.

===================================

via OUP Blog by James W. Cortada

Literacy in the United States was never always just about reading, writing, and arithmetic. Remember in the 1980s and 1990s the angst about children becoming “computer literate”? The history of literacy is largely about various types of skills one had to learn depending on the era in which they lived. Some kept their name, but changed in substance. Map literacy is one of those.

Continue reading

===================================

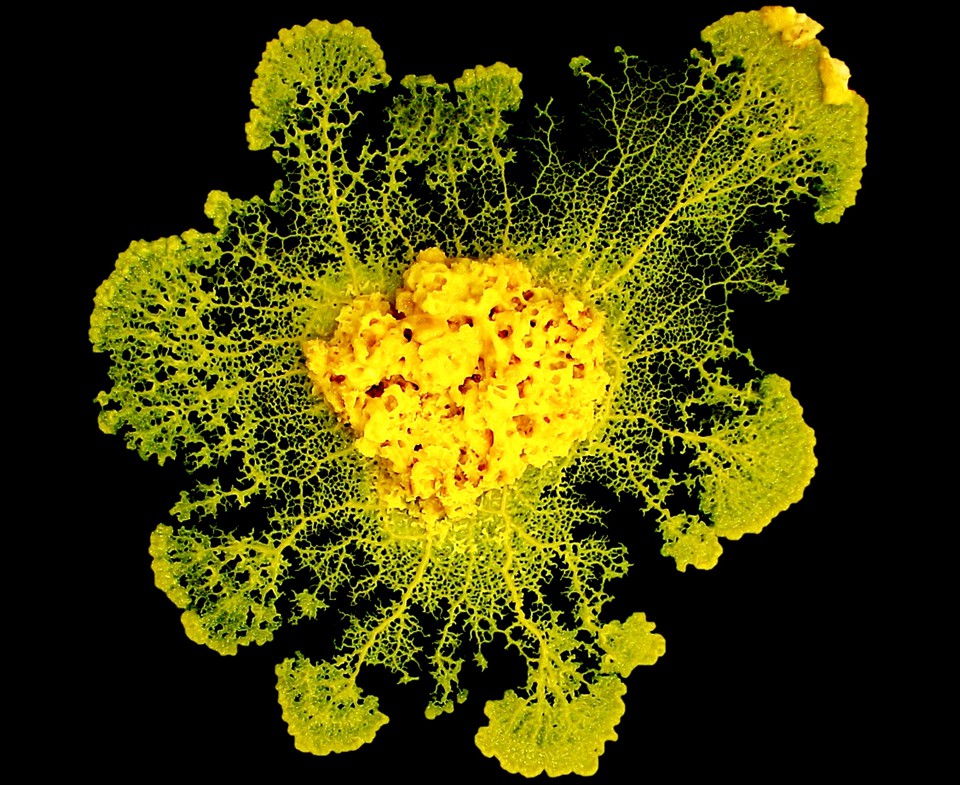

via Medium: Mark Humphries in The Spike

You’re a beautiful machine. Watch:

“To be or not to __”

“Take a look at the lawman, beating up the wrong ___, oh man…”

“You can take your ___ and shove it up your ____”

Automatically, your brain filled in all those missing words. Whether there’s a right answer (‘be’, ‘guy’), or a psychologically insightful one (who got “cantaloupe” and “iguana” for the last one? Just me then), your brain fills in the missing bits. It completes patterns.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Mark Frauenfelder

It looks like a big piece of ice started spinning in a river current. As it rotated, irregular chunks broke off until it formed a circle.

Continue to see video

===================================

via Scholarly Kitchen by David Crotty

The National Library of Scotland received a crumpled plastic bag, filled with fragments of something, that had been found stuffed up a chimney. The bag contained a 17th century map, which had decomposed over the years into a state resembling confetti. The restoration job done by the library is nothing short of astonishing, and the accompanying video below provides an interesting look at the map as a historical document, more important for the stories it tells us about the world at its time than the geography it presents.

Watch the story

===================================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

Historical novelist Debra Daley posts a master guide to the intoxicants of 18th century England, which ranged from modern favorites (laughing gas, cannabis) to historic classics (laudanum) to ratafia, "a sweet liqueur flavoured with peach or cherry kernels," which contained cyanogenic glycosides that broke down into fatal, insanity-causing hydrogen cyanide.

Continue reading

===================================

Seen as less passionate than Emily, less accomplished than Charlotte, Anne is often overlooked. But her governess Agnes Grey is a clear model for Jane Eyre

via the Guardian by Samantha Ellis

Sharp critic of a class-ridden society … Charlie Murphy as Anne Brontë in BBC1’s To Walk Invisible. Photograph: BBC/Matt Squire

Anne Brontë started writing her first novel some time between 1840 and 1845 while she was working as a governess for the Robinson family, at Thorp Green near York. I imagine she must have made her excuses in the evenings, and escaped the drawing room, where she had to do the boring bits of her pupils’ sewing, and often felt awkward and humiliated – excluded from the conversation because she was not considered a lady, yet not allowed to sit with the servants either, because governesses had to be something of a lady, or how could they teach their pupils to be ladies?

Continue reading

===================================

via The New Statesman by Lynne Truss

Vulgar Tongues: an Alternative History of English Slang gathers material from a mind-boggling range of sources – but still leaves you wanting more.

Continue reading