via the Big Think blog by Matt Davis

- Nearly all domestic animals share several key traits in addition to friendliness to humans, traits such as floppy ears, a spotted coat, a shorter snout, and so on.

- Researchers have been puzzled as to why these traits keep showing up in disparate species, even when they aren't being bred for those qualities. This is known as "domestication syndrome."

- Now, researchers are pointing to a group of a cells called neural crest cells as the key to understanding domestication syndrome.

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this special guest blog post, Ana Sampson discusses six female poets whose poetry has been forgotten (even if they are remembered for something else!)

In 2017, I decided that I wanted to read an anthology of poems by women spanning many centuries and diverse points of view. There had been nothing of this nature published for at least the last two decades. I began to research my own, in the process discovering a rich seam of wonderful work I had never read before, though some of the names were already familiar. Here are six women who wrote fantastic poetry – though it is not what they are remembered for today.

Continue reading

==============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Tim Parks in AEON

In an age when so many people are at a loss to give life meaning and direction, Giacomo Leopardi is essential reading

Imagine you spend your childhood almost entirely in a library, your father’s library. There are thousands upon thousands of volumes, most of them old, many in foreign languages. Your native language is Italian, but by age 10 you are reading in Latin, Greek, German and French. English and Hebrew are next on the list.

Why are you doing this? Your father is ambitious for his firstborn son. He wants you to be a priest. At 12, you receive the tonsure, meaning your hair is cut like a monk’s to dedicate you to God. You are dressed in a cassock. More than a priest, or even a bishop, your father wants you to be a champion of Christianity, a theologian; you will use your learning to refute false doctrines, liberalism, atheism.

Your progress is astonishing. At 14, your tutors tell you they have nothing more to teach you. Left to your own devices, you limber up with translations from the classics, philological commentaries, philosophical dissertations, tragedies, epigrams, History of Astronomy and a Life of Plotinus, until, at age 17, you embark on your first major work: an Essay on the Popular Errors of the Ancients. ‘The world is full of errors,’ you write in the opening line, ‘and man’s first task must be to know the truth.’ Your father is delighted. But the truth, as time slips by among the ‘sweat-stained pages’ in the book-lined rooms, is that the more you write about gods and ghosts and mythical monsters, the more attractive these stories begin to seem, especially when compared with the Christian rationality that was supposed to sweep them away.

Continue reading

==============================

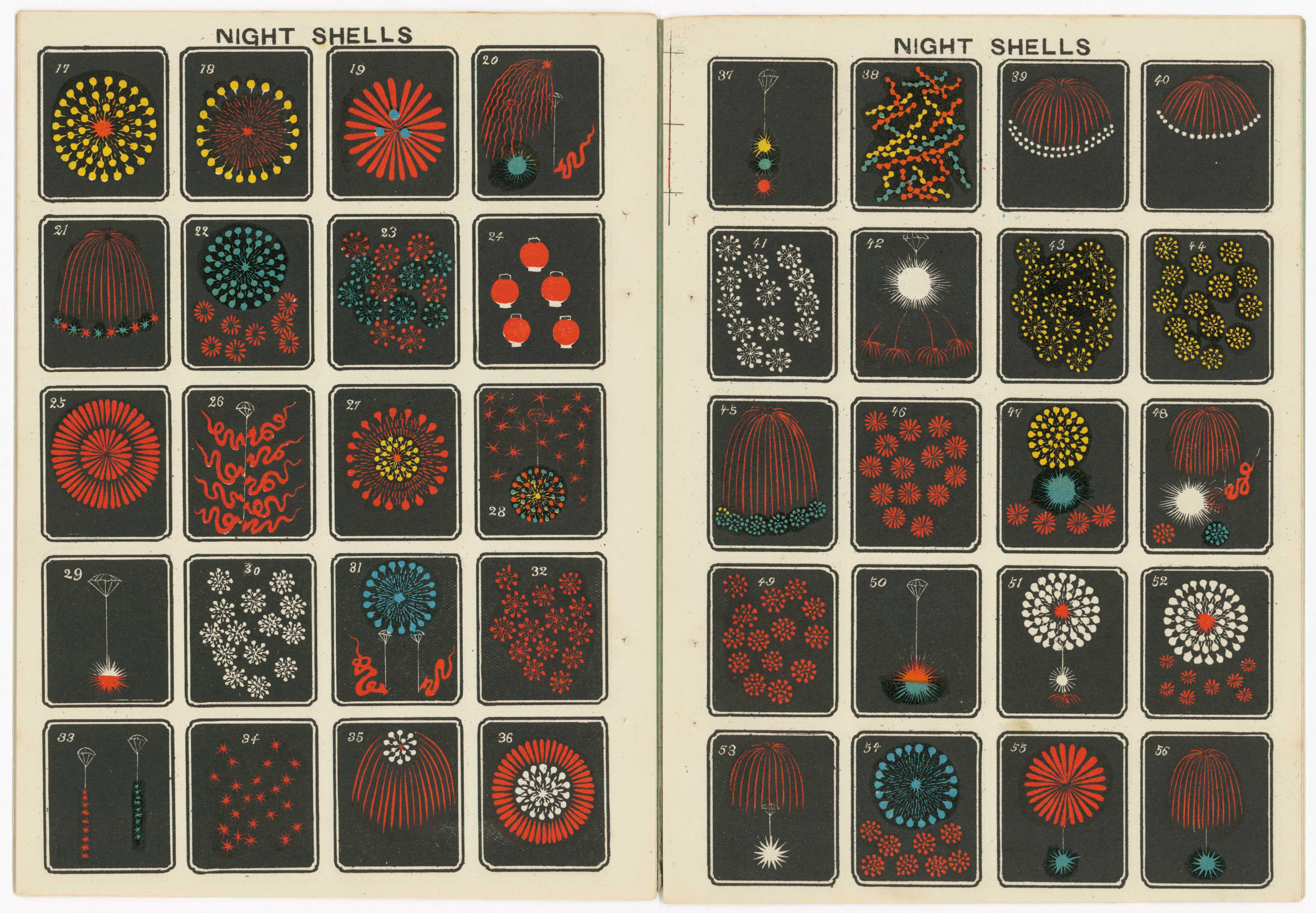

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

The Yokohama Board of Education has posted scans of six fantastic catalogs from Hirayama Fireworks and Yokoi Fireworks, dating from the early 1900s. The illustrated catalogs are superb, with minimal words: just beautiful colored drawings depicting the burst-pattern from each rocket.

Continue reading/looking [but don’t bother with the link Cory provides unless you read Japanese]

==============================

via the OUP blog by Madeline Woda

“Hocgracili” by Alatius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Between the fall of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century and the collapse of the east in the seventh, the remarkable era of the Emperor Justinian (527 – 568) dominated the Mediterranean region. Famous for his conquests in Italy and North Africa and for the creation of stunning monuments such as the Hagia Sophia, his reign was also marked by global religious conflict within the Christian world.

Continue reading

==============================

Quantum particles are mysterious and difficult to track down, but neutrinos may be the most elusive quantum particles yet. The facilities designed to observe neutrinos are feats of engineering, and what they hope to uncover is profound.

via the Big Think blog by Matt Davis

Across the globe, miles beneath mountains, under polar ice caps, and below the ocean are massive facilities filled with sensitive and obscure instruments. They are manned by scientists working to snatch signs of nearly undetectable particles that could, all at once, be used as a tool for understanding supernovae, the impossibly dense interiors of stars, and potentially provide insight into the origin of the universe. These facilities detect neutrinos, at once the most ubiquitous particle we know of and the most difficult to detect.

Continue rerading

==============================

via Interesting LIterature

Aesop’s fable of the fox and the grapes is among the most famous of all of Aesop’s fables. What does this little tale mean? And what common everyday phrase did it inspire?

Continue reading

==============================

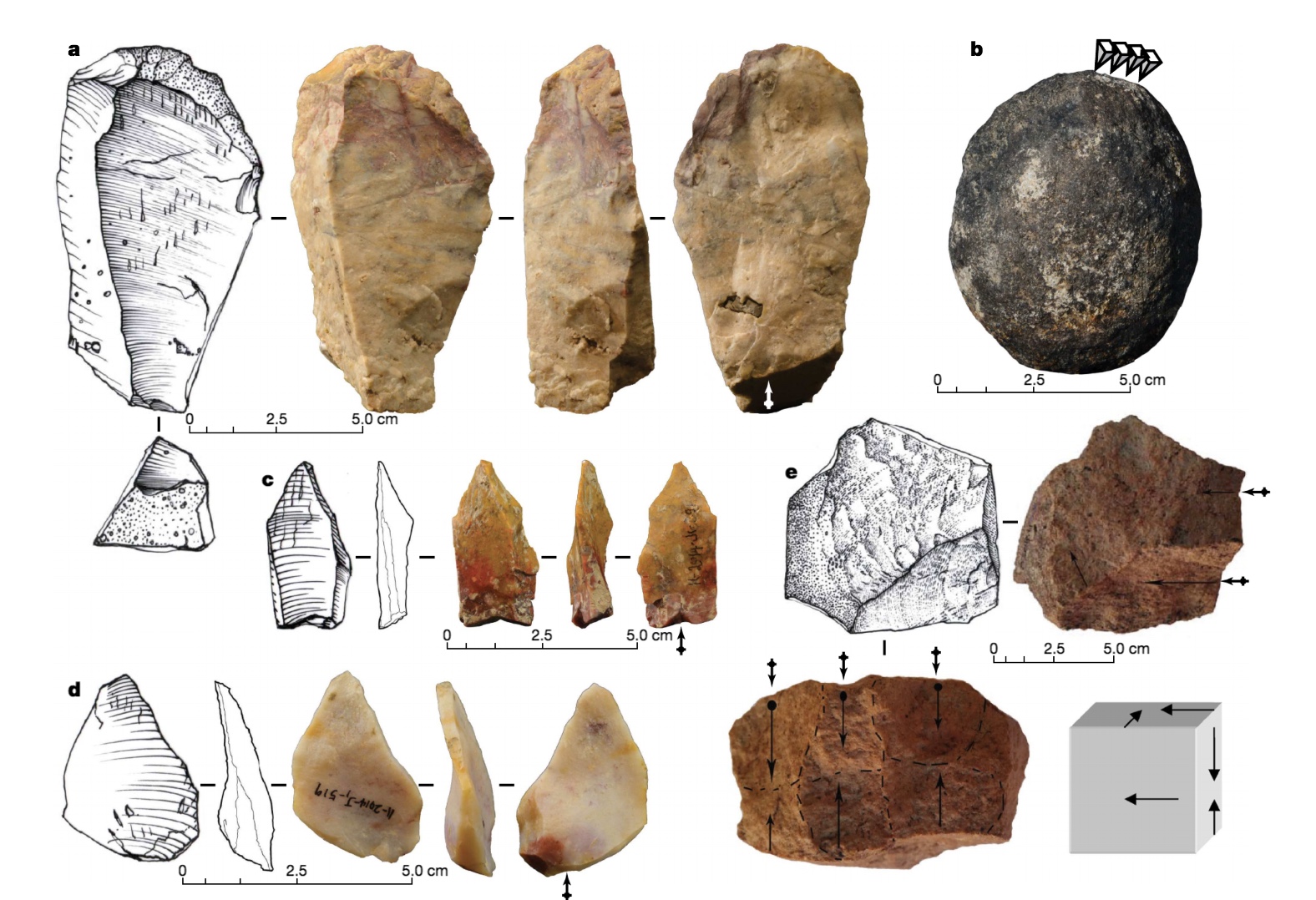

via Boing Boing by Andrea James

Archaeologists have determined from a butchered rhinoceros that the Philippine island of Luzon was inhabited by hominins hundreds of thousands of years before anatomically modern humans arrived.

Continue reading

==============================

via About History by Alcibiades

The Holy Alliance is a conservative union of Russia, Prussia and Austria, created to maintain the international order established at the Vienna Congress (1815). To the declaration of mutual aid of all Christian princes, signed in October 1815, subsequently all monarchs of continental Europe, except England, the Pope and the Turkish sultan gradually joined. Not being in the exact sense of the word a formalized agreement of the powers that would impose certain obligations on them, the Sacred Union nevertheless entered the history of European diplomacy as “a cohesive organization with sharply outlined clerical-monarchist ideology, created on the basis of suppression of revolutionary sentiments”.

Continue reading

==============================

via the OUP blog by Subrata Dasgupta

‘Colossus’ from The National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Most practicing scientists scarcely harbor any doubts that science makes progress. For, what they see is that despite the many false alleys into which science has strayed across the centuries, despite the waxing and waning of theories and beliefs, the history of science, at least since the ‘early modern period’ (the 16th and 17th centuries) is one of steady accumulation of scientific knowledge. For most scientists this growth of knowledge is progress. Indeed, to deny either the possibility or actuality of progress in science is to deny its raison d’être.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment