via Interesting Literature

A commentary on one of Joyce’s shortest Dubliners stories

‘Araby’ is one of the early stories in James Joyce’s Dubliners, the 1914 collection of short stories which is now regarded as one of the landmark texts of modernist literature. At the time, sales were poor, with just 379 copies being sold in the first year (famously, 120 of these were bought by Joyce himself). And yet ‘Araby’ shows just what might have initially baffled readers coming to James Joyce’s fiction for the first time, and what marked him out as a brilliant new writer. But before we get to an analysis of ‘Araby’ (which can be read here), a brief summary of the story’s plot – what little ‘plot’ there is.

Continue reading

==============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Hugo Drochon in Ther Irish Times

Sue Prideaux’s biography is the type you would stay in bed all Sunday just to finish

Explosive: Friedrich Nietzsche. Photograph: Culture Club/Getty Images

On the morning of January 3rd, 1889 a half-blind German professor, sporting a luxurious moustache, left his lodgings on the third floor of Via Carlo Alberto 6 in Turin. He was used to taking his daily walk through the famous arcades of the city, which shielded him from the light, and along the banks of the river Po. He would walk up to five hours a day, which explained his muscular frame: somewhat in dire contrast to the various illnesses that notoriously plagued his life.

But that day he did not get very far. He walked less than 200m to the Piazza Carignano, and what happened next is the stuff of legend: seeing an old recalcitrant horse being flogged mercilessly by its owner, the professor threw his arms around the horse to protect it – perhaps even whispering “Mother, I have been stupid” in its ear (how can anyone have heard that?) – and collapsing. He was saved from being escorted by two policemen to the asylum by his landlord, Davide Fino, who brought him home. We might never know exactly what happened on that fateful day, but one thing is certain: the productive and intellectual life of the great philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had come to an end.

Continue reading

==============================

via The National Archives Blog by Charles Green

A sketch of Walter Raleigh on the scaffold. Creative Commons NYPL digital gallery, c. 1860.

Ask people about Walter Raleigh and they’ll probably think, if not of a bicycle, of Clive Owen in Elizabethan garb, throwing his cloak over a puddle to spare Queen Elizabeth’s (Cate Blanchett’s) royal toes, or handing out grubby potatoes to be nibbled at by her sheepish advisors. Sadly, as a new biography of Raleigh points out, it’s possible that neither of these things actually ever happened.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

Salim Fadhley writes, "Portals of London, an urban exploration blog, presents an alternative geography of London. It's a catalog of the weird, decrepit and slightly crumpled - things the author posits might plausibly be portals to alternative universes, but then again might not."

Fascinating stuff there.

==============================

via About History

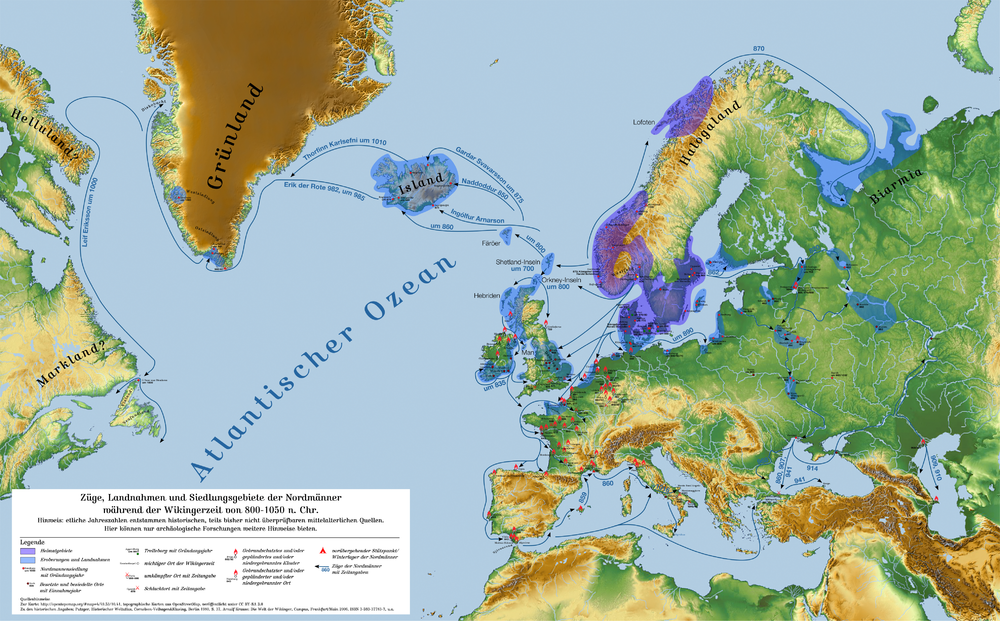

During the Viking Age (9th — 11th centuries), Scandinavian Vikings traveled from Ireland to Russia, engaging in trade, hunting, and robbery. Around 860, the Vikings discovered an island, calling it “ Iceland ” (“Ice Country”), and founded a number of colonies there. While making frequent voyages to the West, the Vikings are now considered to be the first Europeans to visit America, in addition, during the Viking Age, the first genetic contact between Europeans and North Americans also occurred.

Continue reading

==============================

via the New Statesman by Naomi ALderman

Horrifying, mysterious and sentient, our guts are the link between life and death – and if we understood their power we might be happier

The proximity of the anus to the genitals, Freud tells us, is the source of much if not all human neurosis. It’s fashionable to distance oneself from Freud these days, to say “I wouldn’t go that far” and “of course Freud was sex-obsessed”. But I would go that far, and most humans are sex-obsessed.

The gut, frankly, is a problem. What it does is not only mysterious and puzzling – as are all our internal organs – but also difficult for us to bear. And when we start to think about the symbolism of the gut, we might understand what Freud meant.

Continue reading

==============================

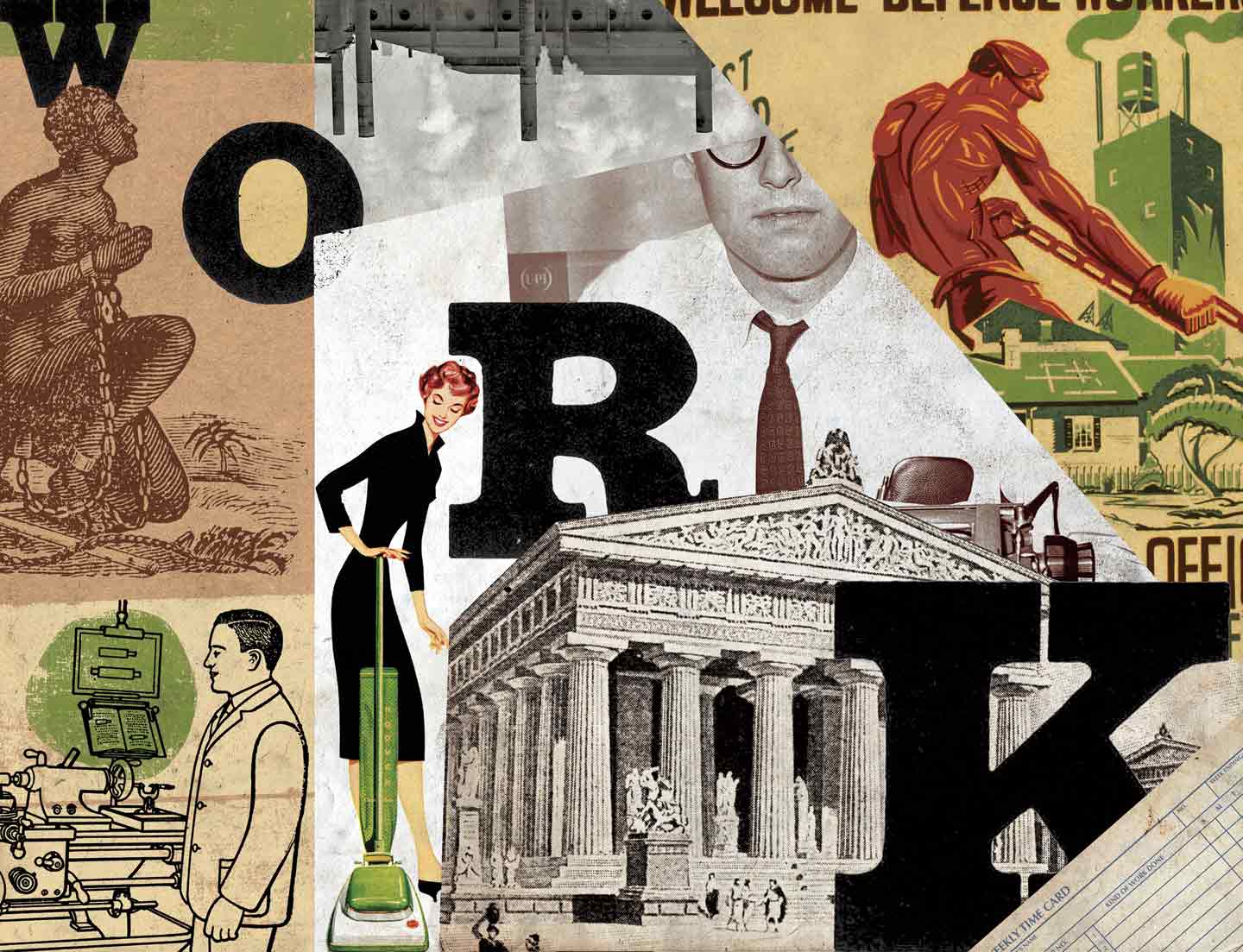

The evolution of work.

via Arts & Letters Daily: Gabriel Winant in The Nation

Illustration by Tim Robinson.

Review of Work: the Last 1,000 Years by Andrea Komlosy

“If you’re old enough to read this,” wrote the great blue-collar poet Philip Levine in 1990, “you know what work is.” What could be more obvious and more concrete than work? It’s your cubicle, your backache, your boss. Good or bad, it needs little explanation. Even to talk about it too much off the clock is to be a bore. It’s just there. Per the infamous American small-talk formulation, it’s simply what one does.

Over recent years, however, the definition of work has become more complicated, as a host of debates have flared up around it. What kinds of activity deserve recognition and reward, and what kinds do not? Which forms of labor create value, and which ones absorb it? Socialist feminists have long insisted that housework is work and should be paid, and a new generation of feminists have extended this insight: When women are expected to console and cheerlead in everyday life, isn’t this a kind of unpaid work? It’s certainly draining. The logic of this argument, in turn, travels from informal caregiving to the official caring industries: Why is it a teacher’s job to buy supplies for her students, instead of the responsibility of the employer? And why must a nurse exhaust herself on the job to make up for corner-cutting management decisions?

Continue reading

==============================

Researchers find the “neural clock” that orders and timestamps experiences and memories.

via the Big Think blog by Paul Ratner

Given the importance of time in running our lives, we don’t really know enough about its ultimate nature. Is it a construct of our mind? Or is it something that is an absolute effect of nature that is independent of our perception of it? Now researchers at the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience in Norway took our understanding of time's mysteries a big step further. They discovered a network of brain cells that maintains the brain’s sense of time by stamping our experiences and memories.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle revisits a classic study of modernist culture and snobbishness

John Carey’s The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880-1939 was published in 1992, over a quarter of a century ago now. The book explores how writers of the early twentieth century – intellectuals as such H. G. Wells, Virginia Woolf, Wyndham Lewis, E. M. Forster, and others – conceived of, and wrote about, the majority of their fellow human beings (the ‘great unwashed’ to use Bulwer-Lytton’s phrase), in disparaging and often jaw-droppingly unsympathetic terms. Carey’s book also shows how this idea of ‘the masses’ was useful to the intellectuals, such as the modernists, in providing them with a mainstream populism which they could then set themselves up in opposition to.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Andrea James

This broadclub cuttlefish like to prowl the Indonesian reefs for crabs, which it then hypnotizes with its remarkable skin before grabbing and eating.

Continue reading and yes, there is a video to watch

No comments:

Post a Comment