The strange life and curious sustainability of de facto states

via Eurozine by Thomas de Waal

Tiraspol, Transnistria. Source: Flickr

We all have a postal address, where a letter or a postcard can be sent. A house number, a street, a town and a country give each of us a personal geography that allows anyone in the world to communicate with us. Except some of us do not. A small category of people in the world do not have an international postal address because their countries do not belong to the world’s postal system – and by extension the common international space. They are global anomalies and their residents are in many ways second-class world citizens. How do we define the status of these de facto states and, more importantly, the people that live there?

Continue reading NOTE: It’s a long read but I found it fascinating.

==============================

via the New Statesman by Richard Overy

Two wings good: rocket-armed Swordfish planes on a training flight in 1944

If the Swordfish has lived on among British legends of the Second World War, the man whose name the aircraft bore has not.

The Fairey Swordfish biplane, as every schoolboy knows, was an oddity of the Second World War, when the skies were dominated by fast and deadly monoplanes. Its obsolescence might have confined it to the historical scrap-heap were it not for the chance encounter one Swordfish had with the German battleship Bismarck as it tried to evade detection and make for a German-controlled port on the French coast. The aircraft did enough damage with its torpedo to slow the great ship down and it was finished off shortly after by Royal Navy warships.

Continue reading

==============================

via Arts & Letters Daily: David Paineau in the Times Literary Supplement

We are living in new Bayesian age. Applications of Bayesian probability are taking over our lives. Doctors, lawyers, engineers and financiers use computerized Bayesian networks to aid their decision-making. Psychologists and neuroscientists explore the Bayesian workings of our brains. Statisticians increasingly rely on Bayesian logic. Even our email spam filters work on Bayesian principles.

It was not always thus. For most of the two and a half centuries since the Reverend Thomas Bayes first made his pioneering contributions to probability theory, his ideas were side-lined. The high priests of statistical thinking condemned them as dangerously subjective and Bayesian theorists were regarded as little better than cranks. It is only over the past couple of decades that the tide has turned. What tradition long dismissed as unhealthy speculation is now generally regarded as sound judgement.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Big Think blog by Philip Perry

At one point during the Neolithic era, the Y-chromosome in our species became far less diverse. Called the Neolithic bottleneck, the reason for it may have finally been revealed.

The Neolithic period or “New Stone Age,” developed at different times in different regions, but is generally thought to have taken place between 7,000-9,000 years ago. An important era in human development, this time period is best known for the Neolithic revolution. Here, humans began to take part in large-scale agriculture, domesticating large herds of animals, building megalithic architecture, and using polished stone tools.

Then, starting around 7,000 years ago and taking place over the next two millennia, something odd happened. The diversity of the Y-chromosome plummeted. This took place across the continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe. It’s the major reason why humans are 99.9% identical in genetic makeup today. The Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck (as it’s called) has stymied anthropologists and biologists since it was first discovered in 2015. Now, the mystery may have been solved.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

‘As imperceptibly as grief’ describes the passing of summer, which happens so slowly and subtly that it is almost missed. But this isn’t necessarily a bad thing: it happens ‘as imperceptibly as Grief’, suggesting that something is coming to a close but brighter times are just coming into view. An unusual take on the onset of autumn, admittedly, but one of the many reasons why Emily Dickinson’s poems repay closer analysis: they avoid the obvious take on things, and offer a strikingly individual perspective on the natural world.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

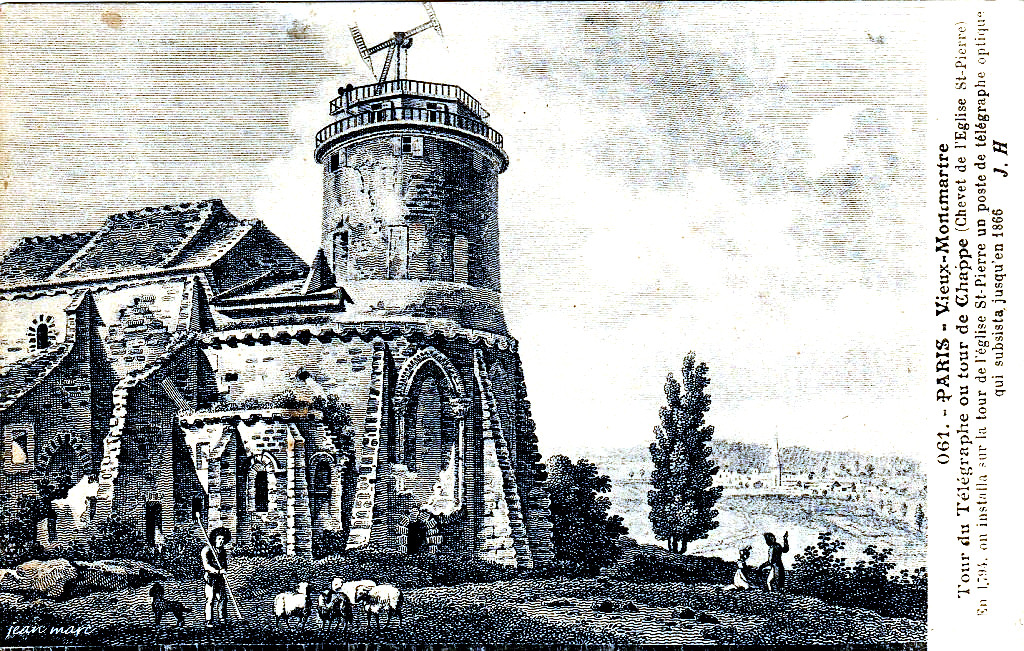

France created a national mechanical telegraph system in the 1790s; in 1834, a pair of crooked bankers named François and Joseph Blanc launched the first cyberattack, poisoning the data that went over the system in order to get a trading advantage in the bond market.

Continue reading

==============================

via the OUP blog by Peter Kornicki

Page from an 11th-13th century chrysographic manuscript edition of the “Golden Light Sutra” (Suvarnaprabhasottamaraja Sutra) written in Tangut by BabelStone. Public domain via Wikimedia

You don’t have to learn a new script when you learn Norwegian, Czech, or Portuguese, let alone French, so why does every East Asian language require you to learn a new script as well? In Europe the Roman script of Latin became standard, and it was never seriously challenged by runes or by the Greek, Cyrillic, or Glagolitic (an early Slavic script) alphabets. You still have to learn the Greek alphabet for Greek, or the Cyrillic alphabet for Russian, Bulgarian, and Serbian, but they are the only exceptions. On the other hand, in East Asia today, the logographic script based on the Chinese characters is used in China, while Korean uses the indigenous han’gŭl alphabet, Japanese uses a mixture of Chinese characters and two different syllabaries, Vietnamese uses the roman alphabet, and Mongolian uses the Cyrillic alphabet.

Continue reading

==============================

via the Guardian by Ian Sample Science editor

The oldest known case of dandruff has been identified in a small feathered dinosaur that roamed the Earth about 125m years ago.

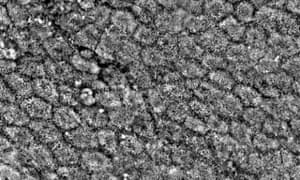

Prehistoric dandruff found on the skin of a microraptor dinosaur. Photograph: Maria McNamara at University College Cork

Paleontologists found tiny flakes of fossilised skin on a crow-sized microraptor, a meat-eating dinosaur that had wings on all four of its limbs.

Tests on two other feathered dinosaurs, namely beipiaosaurus and sinornithosaurus, and a primitive bird known as confuciusornis, also revealed pieces of fossilised dandruff on the animals’ bodies.

The prehistoric skin flakes are the only evidence scientists have of how dinosaurs shed their skin. The material shows that rather than losing their outer layer in one piece, or in large sheets, as is common with modern reptiles, the feathered dinosaurs adapted to shed their skin in tiny flakes.

Continue reading

==============================

via About History by Alcibiades

The history of Mali starts in 1050, when the Almoravids attacked the Ghanan Empire, when Baramendana is recorded as ruler of a small Mali Kingdom. He was a Muslim and made a pilgrimage to Mecca, something that every ruler of Mali was required to do. After the death of Abu Bekr in 1087, several kingdoms gained independence from Ghana, including the Mali Kingdom. Not much is known about the rulers after this, until c. 1200, when the Susu kingdom under the rule of Sumanguru attacked the Mali Kingdom and killed all the heirs to the throne, except a young crippled child by the name of Sundiata, who was exiled. However, Sundiata managed to recover and raised an army.

Continue reading

Fortunately this short item includes a map which helped me to position Mali on the African continent.

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle travels back over four millennia to find the oldest surviving epic poem

What’s the oldest epic poem in the world? Did it all begin with Homer’s Iliad? In one sense, we can grant this as an acceptable proposition, but if we wish to trace the true origins of ‘the epic’ as a literary form, we need to go back considerably further into the very hazy early years of literary history.

For the epic began in the Middle East with works like The Epic of Gilgamesh, the tale of a Sumerian king who possesses seemingly inhuman strength and who meets his match in the mysterious figure of Enkidu; this poem also, notably, features the Flood motif we also find in the Book of Genesis. But even Gilgamesh wasn’t the first epic. That honour should probably go to The Descent of Inanna.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment