via the Guardian by Donna Ferguson

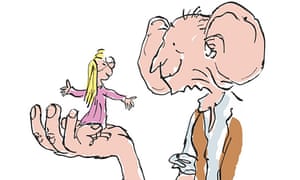

‘Dahl, in his language as much as in his characters and his plots, always has a twinkle in his eye’ … The BFG. Illustration: Quentin Blake

A new book by lexicographer Susan Rennie collects the author’s nonsensical insults and expletives, celebrating ‘words that push the boundaries a little bit’

If a small child were to walk up to the lexicographer Susan Rennie in the street and call her a slopgroggled grobsquiffler, she would know exactly how to reply. “You squinky squiddler!” she would shout. “You piffling little swishfiggler! You troggy little twit! Don’t you dare talk pigsquiffle to me, you prunty old pogswizzler!”

Either that, or she would thank the child profusely for taking the time to read her latest book, Roald Dahl’s Rotsome and Repulsant Words. Ostensibly a children’s dictionary of Dahl’s insults and expletives, the book also offers a chance to explore and analyse Dahl’s creative use of language, encouraging Dahl lovers of any age to have fun playing with his naughty-sounding words.

Continue reading

==============================

via ResearchBuzz: Firehose: Heather Dockray on MashableUK

IMAGE: GETTY IMAGES

Back in 2012, writer Jack Chang coined something known as "the slow web." Similar to the slow foods movement, the idea of the slow web movement was to decelerate the pace in which readers consume content: "slow web" consumers would read full length articles, keep open tabs to a minimum, and otherwise spend meaningful time on the internet, instead of just time.

Continue reading

==============================

via the OUP blog by Michael Neiberg

Europe map 1919. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

National self-determination was supposed to be the answer to the so-called “ethnic problem” of the 19th century. The prewar, multi-ethnic Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires, all on the wrong side of history, had disappeared at the end of the First World War never to return. In their place would come relatively homogenous nation-states that would, in theory, reduce the ethnic tension that had undermined the stability of Central Europe and the Balkans. Once each nation possessed its own internationally-recognized borders and resources, Europeans should have a greater incentive to cooperate and fewer reasons to compete.

Continue reading

==============================

The case for Chopin

via Arts & Letters Daily: Terry Teachout in Commentary Magazine

Of the well-known composers of the 19th century, Fryderyk Chopin (as his name is spelled in Polish, his native tongue) is the only one whose complete works continue to be played regularly—indeed, without cease. Most of the pianists who had major international careers in the 20th century performed and recorded such staples of his catalogue as the A-flat Polonaise (“Heroic”) and the B-flat Minor Piano Sonata (“Funeral March”). They remain central to the repertoires of the rising generation of virtuosi, just as they have always been beloved by concertgoers. Yet Chopin’s phenomenal popularity was long viewed with suspicion by critics, in part because his compositions, without exception, all make use of the piano; in addition, most of them are solo pieces that are between two and 10 minutes in length. No other important classical composer has worked within so tightly circumscribed a compass.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

A short introduction to the tale of the three wishes

The pattern of three is deeply embedded in the structure of the fairy tale. Numerous fairy stories, from Goldilocks and the three bears to Rumpelstiltskin to the story of Snow White (to name but three) rely in part on the tripartite narrative structure (three bears, three bowls of porridge, three visits to the house, three nights, and so on). But perhaps the most concentrated example of this patterning is the fairy tale titled ‘The Three Wishes’, where the entire story hinges on the granting of three wishes to a character.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

Irene Posch and Ebru Kurbak's Embroidered Computer uses historic gold embroidery materials to create relays ("similar to early computers before the invention of semiconductors") that can do computational work according to simple programs; it's installed at the Angewandte Innovation Lab in Vienna.

==============================

via the Big Think blog by Paul Ratner

Eight-dimensional octonions may hold the clues to solve fundamental mysteries.

Physicists discover complex numbers called octonions that work in 8 dimensions.

The numbers have been found linked to fundamental forces of reality.

Understanding octonions can lead to a new model of physics.

Continue reading

Hey there! I managed an O-Level in physics but dropped it in favour of chemistry at A-Level. No mention of models back then let alone new models.

==============================

via the OUP blog by Jack M. Gorman

Nerve Cell by ColiN00B. CC0 via Pixabay.

When I was in medical school, my fellow students and I all dreaded a single course, taught then in the second year—neuroanatomy. At my school, we had two famous neuroanatomy professors who had written competing textbooks on the subject and clearly disliked each other. One was known to be eccentric and the other mean. But the reason we dreaded the course was that we knew it would challenge the human capacity for memorization to the absolute limit. And given how many things a medical student is required to memorize, we were frightened.

Continue reading

==============================

via Interesting Literature

In this week’s Dispatches from The Secret Library, Dr Oliver Tearle visits a futuristic London that is decidedly medieval

Richard Jefferies, who appears to have been the first person to use the phrase ‘wild life’ to describe the natural world in 1879, is one of England’s greatest ever nature writers. But what is less well-known is that he was also a novelist. If his novels are recalled, it tends to be his book Bevis, a tale featuring a group of young boys who play games and build things and otherwise amuse themselves among the natural world, which is mentioned. Far less celebrated is his work of dystopian fiction, After London, which was published in 1885. The original title of Bevis was going to be After London, suggesting that the two novels have an affinity; but After London offers something starkly different. Ten years before H. G. Wells published his far more famous book The Time Machine, Jefferies was predicting a time in which London had reverted to pre-industrial greenery, much like the London of 802,701 in Wells’s novella has become a vast garden.

Continue reading

==============================

via Boing Boing by Rob Besxhizza

Link through to see several different videos

No comments:

Post a Comment