via The Economist by P.C.

The tensions in the Middle East between Saudi Arabia (ruled by the Sunni Saud family) and Iran (the leader of the Shia camp) have led many commentators to draw parallels with Europe’s Thirty Years War (1618-48). That was a conflict that had devastating consequences for central Europe, with around 20% of the German population being killed. The war had religious roots as the Holy Roman Emperor (initially the Habsburg Ferdinand II) tried to reassert Catholic hegemony over the Protestant areas of the empire. The Reformation had begun in Germany in 1517 with the theses of Martin Luther and many princes of the Empire (which had a quasi-federal structure) had converted to the Protestant cause.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Mark Frauenfelder

Swiss watchmaker Henri Maillardet created the "Ethiopian caterpillar" in 1820 (or thereabouts) for a wealthy Chinese collector. It's covered in gold and encrusted in jewels and peals. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 2010 for $415,215.

Video of it moving is here

===================================

via OUP Blog by Simon Horobin

Tea was first imported into Britain early in the seventeenth century, becoming very popular by the 1650s. The London diarist Samuel Pepys drank his first cup in 1660, as recorded in his famous diary: “I did send for a cup of tee (a China drink) of which I had never drunk before.” The word tea derives ultimately from the Mandarin Chinese word chá, via the Min dialect form te. The Mandarin word is also the origin of the informal word char, heard today in phrases like a nice cup of char. The Chinese origin of the plant is remembered in the idiom not for all the tea in China, meaning “certainly not,” “not at any price,” which originated in Australian slang of the 1890s.

Continue reading

===================================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Mike Newland in Nautilus

Compared to the hectic rush of our bipedal world, a plant’s life may appear an oasis of tranquility. But look a little closer. The voracious appetites of pests put plants under constant stress: They have to fight just to stay alive. And fight they do. Far from being passive victims, plants have evolved potent defenses: chemical compounds that serve as toxins, signal an escalating attack, and solicit help from unlikely allies. However, all of this security comes at a cost: energy and other resources that plants could otherwise use for growth and repair. So to balance the budget, plants have to be selective about how and when to deploy their chemical arsenal. Here are five tactics they’ve developed to ward off their insect foes without sacrificing their own well-being.

Continue reading

===================================

What was rail travel like in 1830?

via The National Archives Blog by Chris Heather

Today we tend to take the railways for granted. If we talk about them at all it is usually to complain about trains being late, overcrowded, or cancelled. Train travel seems to have have lost its magic for many people. Familiarity has bred contempt because for as long as you have been alive there has always been the option of travelling on a train.

But imagine what it must have been like 180 years ago when the first passenger steam train was introduced, and riding at high speed through the countryside was a new and exciting experience.

Continue reading

===================================via The National Archives Blog by Chris Heather

Today we tend to take the railways for granted. If we talk about them at all it is usually to complain about trains being late, overcrowded, or cancelled. Train travel seems to have have lost its magic for many people. Familiarity has bred contempt because for as long as you have been alive there has always been the option of travelling on a train.

But imagine what it must have been like 180 years ago when the first passenger steam train was introduced, and riding at high speed through the countryside was a new and exciting experience.

Continue reading

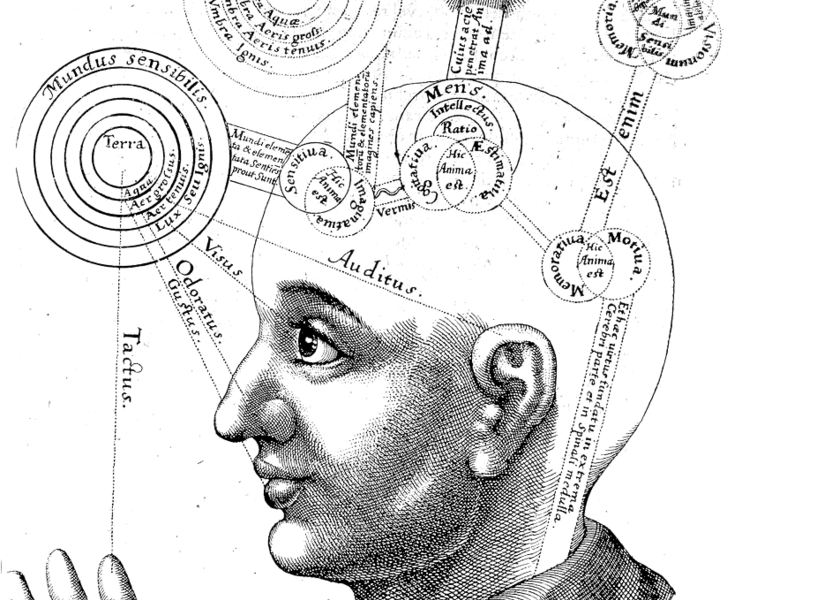

The phosphene dreams of a young Christian soldier

via OUP Blog by Justin Skirry

On a blustery St. Martin’s Eve in 1619, a 23-year-old French gentleman soldier in the service of Maximilian of Bavaria was billeted near Ulm, Germany. Having recently quit his military service under Maurice of Nassau, he was new to the Bavarian army and a stranger to the area. The weather and lack of associates motivated the youth to remain alone in his room for days at a time. It was a comfortable room, warmed against the bitter cold by a porcelain stove. One can imagine that such cozy solitude might provide occasion for the young man to reflect on his course in life. He had studied law at Poitiers and military science at Breda but had yet to decide on a career. Perhaps, he hoped for some guidance as he crawled under the covers for a warm winter’s nap. That young soldier was Rene Descartes and, as legend has it, guidance came on that fateful night of 10-11 November 1619 in the form of three dreams.

Continue reading

===================================

David Hume, the Buddha, and a search for the Eastern roots of the Western Enlightenment

via 3 Quarks Daily: Alison Gopnik in The Atlantic

In 1734, in Scotland, a 23-year-old was falling apart.

As a teenager, he’d thought he had glimpsed a new way of thinking and living, and ever since, he’d been trying to work it out and convey it to others in a great book. The effort was literally driving him mad. His heart raced and his stomach churned. He couldn’t concentrate. Most of all, he just couldn’t get himself to write his book. His doctors diagnosed vapors, weak spirits, and “the Disease of the Learned.” Today, with different terminology but no more insight, we would say he was suffering from anxiety and depression. The doctors told him not to read so much and prescribed antihysteric pills, horseback riding, and claret—the Prozac, yoga, and meditation of their day.

Continue reading

===================================

These 15 Fascinating History Sites Make the Past Come Alive

via MakeUseOf by Saikat Basu

It is difficult to make sense of time isn’t it?

Then let’s pause and reflect how utterly impossible it is to do the same with 5000 years of recorded human history. The mind boggles at the thought. Right now, even the birth of the Internet seems ages ago. The Sumerians captured history in their own way, and we in the digital age are doing it with bits and bytes.

A single genome is spilling the beans on what our ancestors were up to thanks to The Human Genome Project. But some fascinating history websites also manage to combine interactivity with storytelling to bring our past alive. If you didn’t like history in school, you can make up for those poor grades by enjoying the fifteen sites below.

Continue reading

===================================

The exceptional English?

via OUP Blog by George Molyneaux

There is nothing new about the notion that the English, and their history, are exceptional. This idea has, however, recently attracted renewed attention, since certain EU-sceptics have tried to advance their cause by asserting the United Kingdom’s historic distinctiveness from the Continent. In political terms, this argument is dubious – even if the UK were exceptional in various past epochs, this would have little logical bearing on the desirability or otherwise of its participation in future European integration. The fundamental problem with the exceptionalist line is not, however, political illogicality, but historical naivety.

Continue reading

===================================

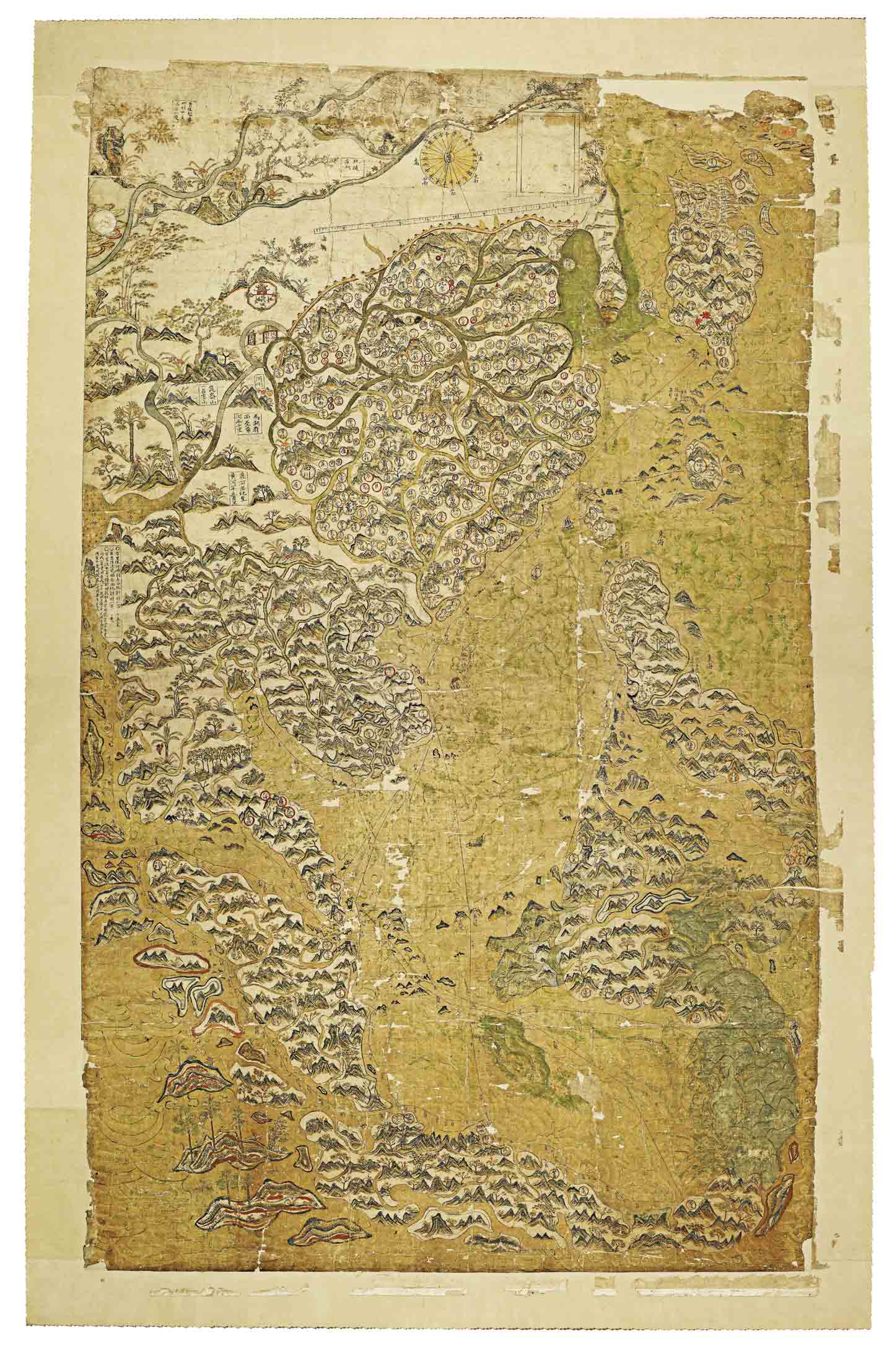

Before Europe’s Intrusion

Via Arts & Letters Daily: Paula Findlen in The Nation

A 17th-century map reinforces what few other than historians of China have known: It was an open and diverse world with a long tradition of maritime commerce.

On a cold, wet day in January 2008, Robert Batchelor decided to take a peek at a map in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, an old and venerable collection founded in 1602 and filled with arcane treasures. Anyone who has ever used the library may recall the oath that all readers are required to take (formerly in Latin, but nowadays in English, I think) not to remove, deface, or injure any of the library’s books, let alone bring in any fire or kindle one – a great temptation in a library originally devoid of any artificial heating source, especially for a generation that had just discovered the lure of Virginia tobacco. Batchelor, a historian of Britain and Asia, was about to fly back to the United States, where he teaches at Georgia Southern University, but this unusual item – “A very odd mapp of China. Very large, & taken from Mr. Selden’s” – beckoned. With the help of the Bodleian’s curator of Chinese collections, David Helliwell, he retrieved it from the bowels of the library. The map was in a fragile, indeed ruinous state, disintegrating on the stiff linen backing that had deformed it during a botched preservation job a century earlier. Helliwell would later recall that he had seen the map before, but without recognizing its full import. Batchelor was enchanted and enthralled. Here was a hand-painted map of East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia and India that raised a myriad of interesting questions.

Continue reading