via 3 Quarks Daily: Rebecca Solnit in Orion Magazine

The four horsemen of my apocalypse are called Efficiency, Convenience, Profitability, and Security, and in their names, crimes against poetry, pleasure, sociability, and the very largeness of the world are daily, hourly, constantly carried out.

These marauding horsemen are deployed by technophiles, advertisers, and profiteers to assault the nameless pleasures and meanings that knit together our lives and expand our horizons. I’m listening to a man on the radio describe how great it is that there are websites where musicians who have never met or conversed or had any contact at all can lay down tracks together to make songs. While the experiment sounds interesting, the assumption sounds scary – that the complex personal, creative, and cultural collaborations of music-making could be unnecessary and you just need the digital conjunction of some skill sets. The speaker seems to believe that the sole goal is the production of songs, sundered from the production of social ties and social pleasure. But music has always been an occasion for people to get together – in rehearsals, nightclubs, parties, festivals, park band-shells, parades, and other social spaces. It is often the soundtrack to bodies in conjunction, whether marching or making love.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Cory Doctorow

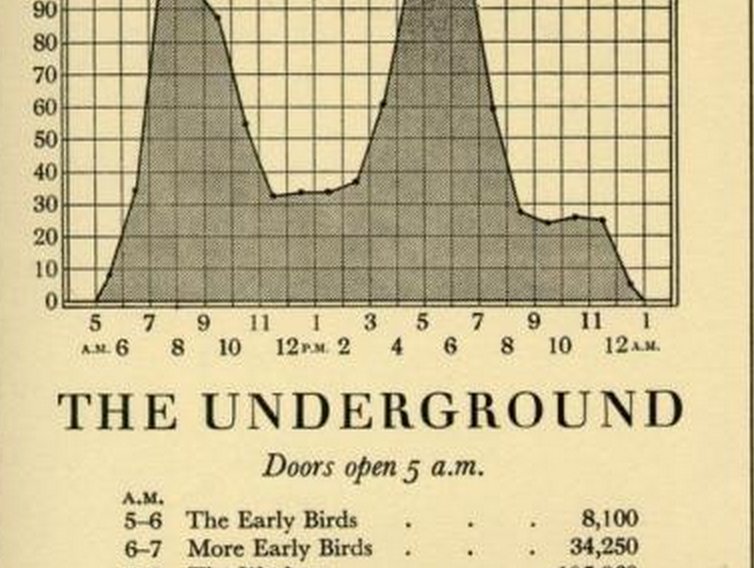

This 1928 London Underground ad is a beautiful and witty example of using data to help people get the best use out of public services. By listing the tube's load at different times of the day, LU helped riders figure out how to avoid crushes, and by making the descriptions funny and insightful, the poster's creators created memorable hooks for putting the info in context.

Continue reading

===================================

via OUP Blog by Emma Smith

Describing her role as the ambitious political wife Claire Underwood in the American TV series House of Cards, Robin Wright recognized she is “Lady Macbeth to [Francis] Underwood’s Macbeth.” At one point in the second series, Claire emboldens her wavering husband: “Trying’s not enough, Francis. I’ve done what I had to do. Now you do what you have to do.”

It’s the equivalent, in the clipped dialogue of the genre, of Shakespeare’s most vehement and brutal image: Lady Macbeth offering to brain her suckling child “had I so sworn / As you have done to this” (1.7.55-9). The Underwoods rework Shakespeare’s ultimate power couple in a modern setting, but violent reactions in the American media to Claire’s characterization show that Lady Macbeth continues to challenge norms of femininity, 400 years after a young male actor first embodied her on the London stage. Those coordinates of sex, ambition, and evil plotted by Shakespeare still resonate. Lady Macbeth is a useful shorthand, as is seen in commentators on Michelle Obama, Hillary Clinton, and many other female public figures, to keep women in their place. “Here’s a question for you,” asked one recent tabloid headline, “what’s the difference between Lady Macbeth and Labour’s Yvette Cooper?” The article went on to suggest there was no difference at all; each would stop at nothing to get power for their husband.

No male politician, however ruthlessly ambitious, is ever called a Macbeth.

Continue reading

===================================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Rebecca Newberger Goldstein in The New York Times Sunday Book Review

The philosopher Sidney Morgenbesser, beloved by generations of Columbia University students (including me), was known for lines of wit that yielded nuggets of insight. He kept up his instructive shtick until the end, remarking to a colleague shortly before he died: “Why is God making me suffer so much? Just because I don’t believe in him?” For Morgenbesser, nothing worth pondering, including disbelief, could be entirely de-paradoxed.

Continue reading

===================================

via Boing Boing by Wink

The history of weapons is a fascinating subject, but none more so than the history of swords and their sharp, pointy or bludgeoning cousins. And this book covers most, if not all of it. Starting from the beginning of primitive stone-age weapons, the book spans over 4000 years of history and covers seven different sections: Classical Weapons, Medieval Weapons, Renaissance Weapons, Age of Sabres, Islamic Weapons, Weapons of the Far East and a Wider World of Weapons. What really makes this book pop is how seamlessly it integrates the use and history of weapons with culture. Many weapons carried far more significance as a symbol than as a fighting tool and the book gives some perspective on the different roles these weapons played. The images were taken at the Berman Museum of World History from their 6000-piece collection, and it shows. There are hundreds of images of beautiful swords, each described in detail from its use to its creator.

Continue reading

===================================

via Research Buzz Firehose

New-to-me: there’s a database of spaghetti westerns! I had no idea. And the oldest movie in the database was made in 1906, so this particular movie subset goes back a lot further than I thought…

Hazel’s comment: This I have bookmarked. Best escapism ever.

===================================

via OUP Blog by John Kelly

Amnesia, disguises, and mistaken identities? No, these are not the plot twists of a blockbuster thriller or bestselling page-turner. They are the story of the word culprit.

At first glance, the origin of culprit looks simple enough. Mea culpa, culpable, exculpate, and the more obscure inculpate: these words come from the Latin culpa, “fault” or “blame.” One would suspect that culprit is the same, yet we should never be so presumptuous when it comes to English etymology. Culprit is indeed connected to Latin’s culpa, but it just can’t quite keep its story straight.

Continue reading

===================================

via 3 Quarks Daily: Nicholas Wade in The New York Times

It may be hard to imagine a ménage à trois, satisfactory to all parties, in which one member tries to dislodge another with a toxic gas and a third eats the offspring of the other two. But such an arrangement exists, and one of its members may even be sitting quietly in your kitchen’s spice rack. The story begins with the Large Blue, a butterfly that lays its eggs on the wild oregano plant. The caterpillar munches on the plant’s flower buds for two weeks and then one night drops to the ground. Most ants forage at noon, but by timing its descent at dusk, the infant caterpillar gets adopted by a red ant known as Myrmica that forages only at day’s end. The caterpillar deceives an ant into thinking it is a stray grub from the ant’s own nest. It does so by adopting the grub’s posture and by exuding a scent that mimics that of the ant’s own species. Taken underground to the Myrmica nest, the adopted caterpillar doesn’t remain a helpless foundling for long. It starts to acquire influence in the ant society by imitating the little clucking sounds made by the ants’ queen. And having gained high status in the nest, it can fulfill the purpose of its visit: to feast on the ants’ larvae. The ants themselves use their larvae as a food source when times are tough, so for their queenly guest to behave like a cannibal may not strike them as all that abhorrent.

Continue reading

Do click through if only to see the illustration which will not paste into here!

===================================

via Arts & Letters Daily: Chris Power in New Statesman

The Prank: the Best of Young Chekhov reveals how Anton Chekhov developed from jobbing hack to master of the short story.

There are, at the very least, three Anton Chekhovs: the doctor, the playwright and the short-story writer. In each field, great achievements sprang from undistinguished beginnings. Chekhov was an average medical student, yet he had numerous triumphs as a doctor, including manning the village clinic when a cholera epidemic struck the area around his estate and his 1890 journey to investigate the prison island of Sakhalin: an ambitious humanitarian mission to make the realities of Siberia manifest to the Russian people. As a playwright, he faltered initially, failing to find anyone willing to produce the turgid melodrama Platonov. Ivanov proved his dramatic talent but The Wood Demon, staged two years later, was savaged and half a decade elapsed before he wrote another play. His final four, however, persist as centrepieces of world theatre.

Continue reading

===================================

via The National Archives by Benjamin Trowbridge

It is 600 [and one] years since King Henry V’s army assembled on the southern coast of England to set sail for the French coast in pursuit of their sovereign’s claim to the French crown. The military expedition to France in 1415 opened a new phase in Anglo-French hostilities that had persisted sporadically for nearly a century; a symptom of a rivalry between the two kingdoms that was much older.

Continue reading

===================================

Sex, hygiene, and style in 1840s Paris

via OUP Blog by René Weis

The young woman who inspired Dumas’s La Dame aux Camélias and Verdi’s Violetta in La traviata conceived at least once in the course of her 23 years. At the time she was in her late teens. During the five years that followed the birth of her baby, between the ages of 17 and 22, she prospered as the leading courtesan of the most glamorous city in Europe. The word ‘courtesan’ is a euphemism for an upper class prostitute, a paid woman who doubled as a trophy exhibit at the theatre and opera. The world of chic Parisian sexuality in the 1840s was simultaneously covert and ostentatious: the more brilliant the appearance of the courtesan, the grander the reputation for wealth and generosity of the buck or ‘lion’ who owned her just then. Only rich and famous men could afford women like Marie Duplessis whose wardrobe and apartment, paid for by the men who kept her, added up to a fortune.

Continue reading

No comments:

Post a Comment